A healthy climate for Swiss homes: The medicalisation of indoor climate in the late 19th century

Department of History and European Ethnology, University of Innsbruck (Austria)

irene.pallua[at]gmail.com

Indoor climate gained attention in Switzerland in the late 19th century as a means to preserve human health. In this context, this essay reflects firstly on related scientific concepts and definitions that were developed within the hygiene movement, as well as their relation to heating technologies. Secondly, it will scrutinise the practical realisation of a healthy indoor climate in the household. It will be shown that the vision of a healthy indoor climate, with the middle-class home as a reference point, conflicted with thrift that shaped the traditional ways of heating, particularly among the poorer classes.

Introduction

One of the most pressing issues related to indoor climate is the high energy consumption for heating and cooling. In the face of global climate change, it is thus a policy goal to reduce the associated emissions, for example, by promoting efficient technologies, the switch to renewables, as well as behavioural changes.1 In the 19th century, in the face of severe epidemics,2 human health was considered to be a major concern related to indoor climate. While before the middle of the 19th century it was mainly a topic for experts, that was put into practice in public buildings,3 after this time a healthy indoor climate was also to find its way into households through domestic science education.4 Its improvement was part of a larger transnational project, the hygiene movement.5

The history of indoor climate is so far reflected in studies addressing only several specific countries and time periods.6 Three of them are briefly discussed here. They offer different approaches to the topic, but each considers the indoor climate as a rather complex, social construct. Architectural historian Witold Rybczynski’s study on the history of comfort addresses the change in indoor climate from the Middle Ages onwards. He stresses the importance of health for configuring indoor climate in the 19th century, and in connection with this, for the evolution of heating and ventilation technologies, and for building methods and standards. The spatial focus of his study is on Britain, the USA, and to some extent France.7 Secondly, Vladimir Janković’s study on the advent of medical environmentalism in 18th century Britain discusses various kinds of air and specific climates as well as their positive and adverse effects on the health of those exposed to them. At the time, the improvement, control, and maintenance of middle-class homes related to comfort, set standards of ambient health. This allowed physicians to identify health risks, that deviated from these standards. Janković points out that social norms, values, and moral principles of the time were embedded in the physicians’ argumentation regarding health risks.8 Finally, Gail Cooper’s analysis of the history of air-conditioning in the USA from 1900 to the 1960s particularly emphasises the roles of experts and consumers in negotiating the “proper” indoor climate. She argues that experts who tried to claim control over indoor climate failed because consumers were ultimately responsible for it.9

These studies all show that indoor climate does not exclusively depend on the energy sources and technologies that are used for controlling it, nor the behaviour of individuals or on experts’ recommendations and expectations. It additionally depends on building standards, knowledge, habits, social norms, shared values, and individual body sensations that vary historically and geographically. . Indoor climate is thus a construct that is negotiated by a variety of actors, reflecting their respective knowledge, aspirations, bodily sensations, and values, as well as the respective material and technological environments, and is generated through everyday practices in the household.10

Building on this existing research and adopting the conceptual approach that they have in common, this essay aims at contributing to a history of indoor climate and its control through heating. Its geographical focus is Switzerland where this topic, with very few exceptions, has received little attention so far.11 It concentrates on the late 19th century when the country was heavily industrialising and urbanising, and places the medicalisation of indoor climate at the centre of interest.

The essay is based on the assumption that the medicalisation of indoor climate was an “invisible energy policy”12 that should lead to a change in energy consumption of households by setting new social norms.13 It firstly asks how experts for hygiene envisioned an ideal indoor climate. In which ways and by which technological means could it be achieved? Secondly, assuming that the middle-class home was the reference point for their vision (as Janković does in his study14) the paper asks if healthy indoor climate was seen as class-specific. Both questions will be answered in the first part of the essay which focuses above all on expert knowledge on indoor climate, as well as on heating technologies used in the late 19th century in Switzerland and their effects on human health.

Since for the hygienists the individual was responsible for his or her health15, but the housewife for that of her family,16 a third set of questions arises, which is dealt with in the second part of the essay: How was a healthy indoor climate to be realised in Swiss homes? Did its realisation reflect hygienists’ recommendations?

To answer these questions the essay is mainly based on two kinds of sources that were intended to construct social norms by educating the public and women in particular.

Firstly, to portray the vision of healthy indoor climate, it draws from textbooks on hygiene published in the late 19th century by scientific authorities that aimed to introduce the topic to the public.17 Secondly, to show how this vision was to be implemented in the homes, it is based on two manuals on housekeeping also written at that time. The first housekeeping manual was named “Das häusliche Glück” (“The Domestic Bliss”).18 It was directed at the education of working-class women and published originally in Germany in 1882 by a Christian Association for Workers’ Welfare, founded by factory owners and social reformers.19 Due to its success,20 it was republished in Basel as a special edition for Switzerland, Austria, and Silesia from 1887 onwards. By 1892, 240,000 copies of this edition had been sold in the respective countries.21 The other housekeeping manual “Wie Gritli haushalten lernt” (How Gritli learns to housekeep”)22 was directed at women keeping a middle-class household. It was written by Emma Coradi-Stahl (1846–1912) a Swiss suffragette and founder of the “Schweizerischer Gemeinnützige Frauenverein” (a Swiss charitable Woman’s Association).23

Back to topThe hygienists’ vision of a healthy indoor climate

Given the increasingly worsening living conditions in cities, and foremost in their working-class districts, which were to be found not only in the major European cities such as London, Paris, Berlin, or Vienna but also in the much smaller Swiss cities,24 creating a healthy environment inside and outside the home was deemed to be necessary.

The growth of the Swiss cities due to the influx of mostly young, unmarried people that came from both rural areas and from abroad in search of an urban industry income25 was rapid and uncontrolled. This led to class-specific spatial segregation, especially from 1880 onwards, with the working class settling close to heavy industries and traffic junctions such as railway stations and ports. In these environmentally degraded areas, large tenement blocks emerged.26 Living conditions in these buildings were poor, as the first municipal housing surveys revealed in the 1890s.27 According to members of the Swiss hygiene movement, these buildings were a breeding ground for contagious diseases and moral decay28 that put the wealthier classes of the population at risk.29

The hygiene movement was a transnational movement that developed towards the end of the 18th century, especially in Britain, where the adverse health effects of industrialization were particularly noticeable.30 From Britain, it spread across the world.31 It consisted of people practising medical professions, engineers, architects, urban planners, educators and local politicians, scientists, national economists and statisticians, but also social reformers who all used their special expertise to achieve the common goal of preserving the health of the human body. To fulfil this goal, the hygienists focused on the individual persons as well as on their surrounding environmental conditions, for example at the level of cities or buildings.32 At the individual level, a person was conceived as able to take care of his or her own health. From the hygienists’ point of view, being responsible for one’s own health meant controlling and regulating the most intimate and mundane aspects of life, such as nutrition, personal hygiene, sexuality, and housing.33

In this context, the home, which can be considered people’s most intimate environment, became the object of domestic hygiene. The health of the family members, however, was considered as the responsibility of the housewife34, even though the built environment and thus the housing conditions were not necessarily ideal.

Heating and ventilation were among the most important aspects of domestic hygiene in the last decades of the 19th century. Thus, heating was not simply aimed at warming a room, but at creating a healthy indoor climate, an “artificial summer of the best and healthiest kind”, as Adolph Wolpert - professor for building hygiene in Nuremberg - wrote in the late 1880s in his textbook “Sieben Abhandlungen zur Wohungshygiene” (“Seven Essays on Domestic Hygiene”).35 Creating an artificial summer meant more than increasing the room temperature with a heating system, but to providing a “fresh summer breeze” through ventilation and a pleasant air humidity “as in a shady place”.36 The parameters of this idealized and healthy summer –air purity, humidity (which I will not focus on here), and temperature– were empirically determined by hygienists in the second half of the 19th century through laboratory experiments37 as well as investigations in hospitals, prisons or educational institutions.38

Scientific enthusiasm for air was nothing new at that time but rather evolved in the context of changing ideas about the structure and functioning of the human body during the Enlightenment. The body was understood by the medicine of the time as a “stimulable machine”, as Philipp Sarasin pointed out in his history of the body.39 Overall, the body and, in connection with it, health and physical well-being took on increasing importance. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, this knowledge of the body was taken up by the hygiene movement and combined with ancient concepts of preventive health care –particularly the Hippocratic humoral pathology and dietetics40– which were based on favourably influencing the controllable “sex res non naturales”.41 The “sex res non naturales” included light and air, the environmental conditions, everything that reaches the body, nutrition, work and rest, excreta, sexuality, as well as sensations and emotions. Through certain practices of self-regulation, especially temperance, but also cleanliness and other hygienic rules, the individual person, initially found in the middle-class, could take care of his own health.42 In this context, indoor air, its properties and its regulation became significant for human health, with a particular focus on air purity.

Cleaning contaminated indoor air: heating and ventilation

According to the ideal of cleanliness that developed in Europe since the 18th century Enlightenment, particularly air purity was regarded as beneficial to human health, in line with the miasma theory that was popular until the end of the 19th century. According to this theory, miasmas –bad, foul-smelling air – were the triggers and carriers of disease. Miasmas appeared both outdoors, where they became noticeable, for example, through the foul-smelling exhalations of water or soil, and indoors. Within a building, miasmas were the result of the physical processes of its inhabitants and their household activities such as space heating, cooking, and artificial lighting.43 Even after the germ theory replaced the miasma theory, the imperative of air purity remained valid. The presence of germs and bacteria as “living dust” indoors seemed to make ventilation even more necessary, as the Swiss physician Jakob Sonderegger wrote in the 1870s in his textbook on hygiene.44

As people contaminated the air, sufficient fresh air, quantified as ventilation rate (volume fresh air/person/time unit) had to be supplied from outside into a building to keep people healthy. Already the French chemist Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743–1794) had realised in the 1770s that the carbon dioxide (CO2) content of indoor air was a decisive marker for its purity.45 This finding was taken up and supplemented by the German scientist and founder of experimental hygiene Max von Pettenkofer in the 1850s. According to von Pettenkofer, however, CO2 was not the only polluter. Nevertheless, it was a good proxy for estimating the contamination level of indoor air by organic matter exhaled and perspired which could not be quantified at the time.46 According to von Pettenkofer’s experiments, a CO2 content over 1000 ppm was not acceptable from a human health perspective. To comply with this upper limit, von Pettenkofer calculated a ventilation rate of 50-60 m3/person/hour.47

In following the requirements for air purity, regular ventilation was given utmost importance by the hygienists, particularly in the cold season, seen as space heating, mostly realised with stoves, would additionally worsen the indoor climate through gaseous emissions and burnt dust.48 Traditionally, however, it has been assumed that heating systems contribute to air purity, at least to some extent, because the combustion process leads to a constant exchange of air. This property was shared by the major technologies of the time, which differed geographically within Europe. While in the eastern, middle, and northern parts closed stoves were used since the end of the 15th century, in its western and southern parts the open fireplaces were preferred. British and French settlers spread the use of the open fireplaces in the US, German and Scandinavian settlers the stoves.49

Accordingly, the preferences for heating technologies varied. In Great Britain, France, and partly in the USA with their moderate climates, for example, using stoves was considered as making the rooms stuffy, uncomfortable, and unhealthy, as stoves did not have such a strong draught as the open fireplaces. Additionally, stoves did not provide the symbolic-psychological meaning of visible fire. Finally, handling an open fire was perceived as easier than a fire enclosed in a stove.50 In Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, however, the draught of the stove traditionally was considered sufficient for providing fresh air. In these regions, heating with open fireplaces was regarded as smoky and as a waste of fuel while rooms remained cold.51 As the famous German Krünitz- encyclopaedia phrased it at the beginning of the 19th century, a stove would never work without a certain circulation of air and “[...]this […] also has the advantage that the air in the room is purified, and all moist and polluted air is removed from the room.”52 Towards the end of the century, Meyer’s encyclopaedia likewise defined both the “artificial heating of rooms” and the “maintenance of clean air in inhabited rooms”53 as thepurpose of a stove.

However, with the spread of the doctrine of domestic hygiene, the uncontrollable draught of stoves or open fireplaces was no longer perceived as sufficient for the provision of fresh air; an additional requirement was added: namely regular and controlled ventilation.54

In public buildings - such as welfare, education, and custody institutions, administrative buildings or theatres, and opera houses - air purity was secured by ventilation systems. In most cases, they were based on thermal convection and were thus connected to central heating, usually to an air heating system.55 Most private households, however, did not have central heating at the time. In the cities of Bern and Zurich in 1896 and 1910, respectively, only two per cent of all dwellings were equipped with central heating.56 It was very expensive and hence warmed the villas and homes of a wealthy minority only.57 For this reason, ventilation systems or air heating systems (that also contributed to ventilation) were rarely found in private households. In the 19th century, the most common heating techniques in Switzerland were tiled stoves and iron stoves heated commonly with wood or, in larger cities, with coal, after the coal trade entered the urban areas from the 1880s onwards.58 In private households, ventilation, therefore, meant regularly opening the windows.59

Temperature and the quality of heat

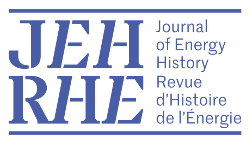

Not only air purity but also the temperature of indoor air mattered and matters for health. Concerning warmth, however, the hygienist Wolpert advocated, for instance, that individual persons also have individual needs and thus recommended certain temperature ranges for certain rooms only, as shown in table 1. These ranges reflected the individual person as well as the intended use of the respective room e.g., the needs of a toddler in a nursery. They were adopted both in encyclopaedias (table 1, column b) and in compendiums for heating and ventilation specialists (table 1, column c). However, it must be considered that the temperature ranges provided by Wolpert and Meyer’s encyclopaedia referred to any kind of heating system, whereas the fixed temperature values provided by Hermann Rietschel - one of the founders of heating and ventilation science - formed the basis for dimensioning different components of a stove, such as its combustion chamber, or of a central heating system, such as the boiler.60

However, hygienists were not only concerned with a specific temperature range, but also with other qualities of heat. It should be mild and evenly distributed vertically in the room to positively affect human health and well-being. Whether such kind of heat could be supplied, depended strongly on the used heating technology. Thus, the above-mentioned hygienists Wolpert, Sonderegger and Flügge, classified heating systems according to their health aspects.

With its excellent heat storage capacity, the tiled stove provided mild warmth by heating the room evenly over a longer period, even though the fire was already extinguished. Sonderegger, for instance, labelled the manufactured tiled stove as an “unsurpassed model” of heating technology, and as a “true friend of the family.”61 On the contrary, Sonderegger termed the industrially produced and cheap iron stove, that was frequently used by the unwealthy62 as “the poor people’s evil friend.63 An ordinary iron stove would initially lead to excessive temperatures and, when the fire died down, to a very quick cooling of the room. Such abrupt temperature changes would disturb the heat regulation of the human body and hence would cause colds and other illnesses. Furthermore, the iron stove polluted the room and the indoor air with ashes, dust, and noxious emissions.

Thus, in the opinion of the hygienists, using a tiled stove, in combination with proper ventilation, would be the best heating technology.64

Indoor climate as a question of Class?

Following their own definitions of a healthy indoor climate, hygienists perceived the climate to be harmful in many Swiss dwellings, above all in farmhouses and the tenements of the working class. They argued that it was too hot and stuffy in the farmers’ “Stube”, even though it was heated with a tiled stove, as was common in the countryside. The climate in the dwellings of the working class is said to have been toxic due to heating with iron stoves. Both peasants and workers were only concerned with temperature without caring about the other qualities of the indoor climate, and particularly about ventilation. Ordinary Swiss people avoided window ventilating for several reasons, as hygienists complained. Firstly, they were afraid of colds, rheumatism, or eye diseases that could be caused by a draught or the night air; a traditional belief that was still supported by some physicians as well as in magazines in the 19th century.65 And secondly, people feared that ventilation would lead to heat losses in winter and to an increase in fuel demand, and fuel costs as a result, which was, of course true.66

Hygienists repeatedly criticized their reluctance to ventilate67 and to demonstrate the innocuousness of fresh air, they referred to the English, who preferred frequent and strong ventilation, the Italian, who commonly ventilated their homes at night, or to the good health of professionals that were constantly exposed to drafts and night air, like night-watchmen, train drivers and stokers.68

In this context, a healthy and thus “good” indoor climate was conceived as the red line separating the “primitive men” from the “civilized men”, as Sonderegger wrote in the 1870s. Primitive people inhabited the countryside and the working-class districts, while civilized people belonged to the educated middle-class.69 His assessment was supported by the systematic housing censuses and dwelling inspections in Swiss cities at the end of the century. The large tenements in the working-class districts of Zurich, Basel, and Berne were cramped, dirty, dark, and damp, poorly ventilated, and barely heatable. Toilets as well as kitchens were to be shared among tenants or even did not exist. Many buildings had no water supply and no connection to the sewage system.70 In the view of hygienists as well as social reformers, the working-class quarters were thus breeding grounds for contagious diseases and posed a great threat to the poor, as well as to the wealthier classes.71 As Sonderegger put it in a nutshell, the “proletarian quarter of a city [...] would be, in health terms, the fuse on the powder keg […].”72

Indoor climate was said to be particularly bad in the overcrowded workers’ dwellings not only because of poor housing conditions, and inadequate heating technologies but also, and above all, because of the habits of its inhabitants, with women being incapable to manage a household properly.73 Viktor Böhmert (1829–1919), a Swiss social reformer, statistician, and economist who surveyed the living conditions of factory workers in the 1870s complained that workers did not ventilate for days or even weeks in winter. Accordingly, he attributed their precarious state of health to the lack of ventilation74 and not at all to the hard factory work, poor housing conditions, or the lack of heating material.

As one of the few hygienists, the German Max von Pettenkofer concluded that there was a connection between unheated rooms and a harmful indoor climate that even ventilation could not eliminate. According to von Pettenkofer, cold rooms simply exchanged less air during ventilation due to the small difference between the outdoor and indoor temperatures. As a result, people not only froze in their barely heated dwellings, which in itself was harmful, but were also exposed to a noxious climate.75 To make a healthy indoor climate affordable for the entire population, von Pettenkofer advocated as early as in the late 1850s that the poor should be provided with fuel in winter, as an effective “sanitäts-polizeiliche Maassregel (sanitary measure) of utmost importance” that would make ventilation more attractive.76 The Swiss hygienist Sonderegger was likewise aware that ventilation led to heat losses and increased fuel consumption, higher heating costs and financial difficulties for the poor. However, he subordinated these problems to health. “Heat is always lost during ventilation, and this costs money. However, it is a simple sum, which is more costly, disease or fuel?” From a “community standpoint,” Sonderegger noted, it would be the disease that would be more costly.77

In this section, it was shown, how hygienists specified healthy indoor climate. In order to maintain the purity of indoor air, a regular exchange of air was seen as necessary, as it was polluted by the physical activities of people. The stove draught or the draught of the chimney, still considered sufficient for air exchange in the early 19th century, were now to be replaced by controlled ventilation, in public buildings by applying technical systems, in private homes by opening the windows regularly. For room climate in heated dwellings, the hygienists not only defined healthy temperature ranges, but the heat also had to be mild and evenly distributed in the room. Only certain stoves, such as tiled stoves, could produce such heat. For the hygienists, indoor climate was class-specific. In their eyes, middle-class homes had a healthy indoor climate, while peasants’ and workers’ homes had a noxious one. Even though poor housing conditions, cheap technology, and a lack of fuel were the main cause for unhealthy indoor climate, the hygienists considered the latter as a result of incorrect individual behaviour. Thus, room climate was conceived as a personal responsibility.

The paragraphs on healthy indoor climate in the textbooks of the hygienists focused primarily on its characteristics and hardly addressed its actual realisation. No instructions on how to heat/ventilate in the proper way were given, although it was acknowledged as “a hard but rewarding task”78. Hence it seems useful to additionally investigate this aspect.

Back to topThrift or Health? The Realisation of Indoor Climate in Swiss households

According to the philosophy of the hygiene movement, the individual person was responsible for his or her own health, and the housewife for the health of the family in the form of good housekeeping.79 Practical advice on household management, including heating and ventilation, was disseminated as part of domestic science education by women’s associations and in household manuals. As in the rest of Europe,80 standardized domestic science education had become institutionalized in Switzerland during the 19th century. The teaching goals of home economics reflected both the promotion of the female cardinal virtues of cleanliness, thrift, and diligence and the promotion of domestic hygiene.81

In the following, I will examine how proper heating and ventilation, which were understood by hygienists as an essential part of domestic hygiene, were conceived in domestic science education using the example of two household manuals that were very well known in Switzerland. One was directed at working-class housewives, the other at women keeping a middle-class household, and particularly at maids. When using sources like housekeeping manuals, etc. it is important to note, however, that they do not reveal much about what the indoor climate in the households was really like or how it was actually controlled, but that they, like the hygienic literature intended to construct social norms.

Saving fuel in the working-class home

“Proper heating is one of the most necessary skills that a housewife must have. Not only the health of the family depends on it to a large extent, but also a lot can be saved or wasted by it.”82 This sentence introduces the chapter on heating in the housekeeping manual “The Domestic Bliss”,83 which was directed at working-class women and was published in the 1880s by a Christian Association for Workers’ Welfare.84

The most pronounced value in this textbook was thrift,85 not only in terms of money and resources which were thought to be inseparable but also in terms of time. Hence, household chores were to be carried out according to a strict schedule which should prevent the housewife from wasting time. At least twice a day, “after breakfast and after lunch,”86 while the housewife was sweeping the rooms, she was to keep all the windows and doors open to let pure, fresh air, “one of the most essential necessities of life”, into the dwelling.87

In contrast to ventilating, the temporal patterns of heating did not follow a strict schedule, but the rhythms of the fire in the stove and the housewife’s perception of room temperatures. Thus, the fire had to be continuously monitored and controlled by smartly opening or closing the doors and flaps of the stove, which was seen as a vital skill that all housewives should learn.88 The housekeeping manual recommended keeping the fire only moderate, except on very frosty days89 When the housewife felt that the room was warm enough, significant savings in fuel could be achieved by covering the fire with wet ashes, as in most cases the embers did not fade. If a strong fire was needed again for cooking or for heating up the room it could easily be rekindled with a handful of sawdust.90 In addition to hay or straw, strips of paper, used tanner’s bark or leftover pieces of coal, sawdust was also the recommended fuel to light a fire cheaply and quickly after cleaning the stove from ashes and fuel residues. Only when the fire was burning properly, the housewife should add fresh fuel.91 Another contribution to saving on fuel was the re-use of incompletely burnt pieces of coal. To this end, the housewife had to sift them from the ashes through “tiresome and dirty work” which she was supposed to do in the morning before reheating the stove.92- If the housewife took this advice on the re-use of coal into account, she could “save a significant amount of money during the year”.93

However, thrift in heating began with the purchase of fuel. This meant, on the one hand, buying fuels (coal, wood, or peat) that were common in the neighbourhood as they were usually cheaper and, on the other hand, getting certain fuels at a specific time. Wood or peat should be bought early in the year as they needed time to dry to burn well. Coal, on the other hand, should only be obtained right before the start of the heating period as its combustion properties would be impaired by long storage.94

The relation of heating and health is only marginally discussed in “The Domestic Bliss”. Healthy heating was primarily linked to the condition of the stove, its maintenance, and cleaning by the housewife, and its regular inspection and professional cleaning by the chimney sweep. Only a functional and clean stove could maintain the purity of the indoor air.95 In addition, excessive heating was criticised as being harmful to health. Unlike in the textbooks of hygienists, however, ventilation was not discussed in relation to heating, but rather in the context of cleaning work. Ventilating the whole dwelling by opening all windows and doors was scheduled twice a day while the housewife was sweeping the rooms since this was a very dusty job.96

The reason why the housekeeping manual does not relate hygienic heating to ventilation is not discussed further. The authors of the “Domestic Bliss” may have taken into account the reality of life of working-class women which was characterised by a tight household budget that prohibited excessive ventilation during the heating season. It is more likely, however, that they assumed the self-evident necessity of ventilating as part of household chores.

The art of heating healthily in the middle-class household

Twenty years later, Emma Coradi-Stahl, a Swiss suffragette and founder of the “Schweizerischer Gemeinnütziger Frauenverein” published the housekeeping manual “Wie Gritli Haushalten lernt “(How Gritli learns to housekeep). It tells the story of Gritli, a young maid from the countryside who is introduced to the management of an upper middle-class household by the lady of the house.

In terms of heating, this housekeeping manual had a similar purpose as “The Domestic Bliss”, namely, to instruct its readers on how to create “the most healthy, comfortable heat with the least possible expenditure of fuel”.97

However, in Coradi-Stahl’s housekeeping manual the creation of a healthy indoor climate was the core of proper heating. Each room of the large house was equipped with a thermometer and a different type of stove, covering all the stoves in use in Switzerland at the turn of the 19th and 20th century: the wood-fired tiled stove, the coal-fired slow-burning stove, a petroleum stove, and a gas fireplace.98 The protagonist of the book, Gritli, was taught to heat properly with all these stoves that had to be operated differently.

In contrast to “The Domestic Bliss”, which recommended only undefined, “moderate” room temperatures, the right temperature was a crucial point in Coradi-Stahl’s housekeeping manual. It depended on the room which was to be heated and its particular use. The head of the household, a professor who mainly worked in his study heated with a tiled stove, preferred a constant room temperature of 19 °C. This temperature should also not be exceeded in the living and dining room. The drawing-room, which was used only temporarily and equipped with a gas fireplace, was to be heated according to the preferences of possible guests. The bedrooms, unlike the other rooms, were to be heated “only in the rarest cases, in severe frost or illness,” with petroleum stoves, but never more than 15° C.99 One of Gritli’s tasks was to check the room temperatures frequently and regulate the room climate accordingly. Consequently, the temporal patterns of heating followed the thermometer. On the one hand, the thermometer was to be used to check whether the intended room temperature was reached. On the other hand, it told the housewife or the maid whether and how to regulate the room temperature. Depending on what temperature the thermometer indicated, it was necessary to add “more wood or better fuel” to raise the room temperature, do nothing, or open the window to lower it.100

Regarding air purity, the housekeeping manual provided specific recommendations for ventilation. In this context, it took a similar position to that of the hygienists, pointing out that the rural population was only concerned about having a warm room and did, therefore, not ventilate. Contrary to her belief, the maid Gritli experienced that proper ventilation - defined here as frequent, short and intensive airing - does not significantly reduce the room temperature. Additionally, Gritli also wished to teach her mother how to ventilate properly, to enable her family in the countryside to live a healthier life.101

Contrary to the housekeeping manual that was directed to working-class women, fuel-saving was hardly reflected in “How Gritli learns to housekeep”. The only reference to fuel savings was a comment on a new type of ash box with an integrated ash strainer with which the residual coal could be easily sieved out of the ash and reused.102

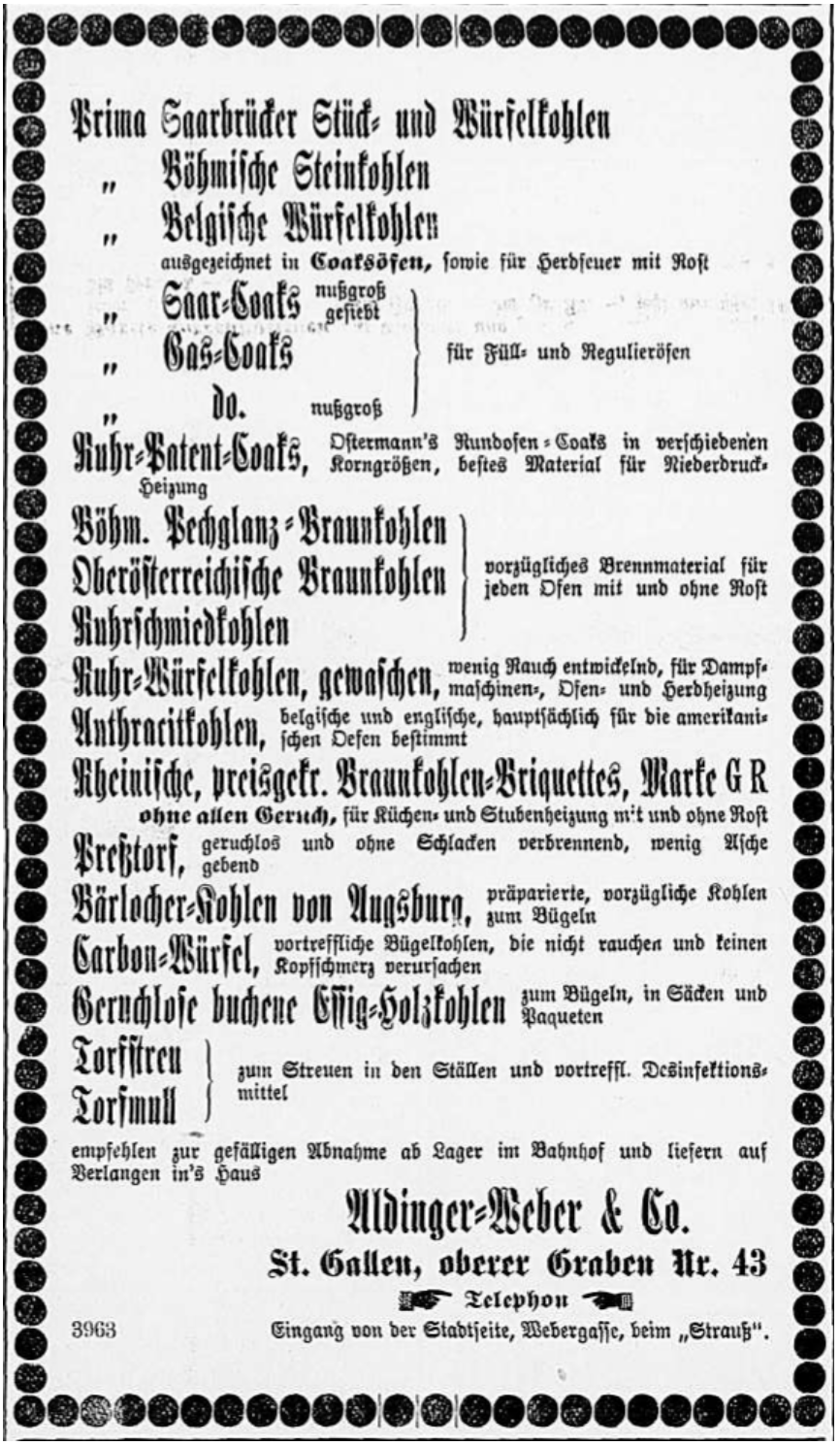

It is worth noting that Coradi-Stahl’s recommendations on heating contradicted certain instructions from stove manufacturers and fuel experts, notably on efficient heating. In the second half of the 19th century, stove manufacturers had increased the efficiency of their products in two ways: Firstly, a stove’s design was oriented to the size and heat requirements of the location in which it was used. Secondly, stoves were increasingly adapted to the combustion of certain fuels, not limited to wood or coal, but oriented towards specific types of coal. For reasons of efficiency, heating and fuel specialists recommended in journals or specialist publications,103 in newspaper advertisements104 as well as in public lectures,105 to always use the most suitable type of coal for the respective heating system.

In an advertisement that was published in a Swiss Newspaper in 1890, and explicitly directed to housewives, the German stove manufacturer Junker & Ruh promoted the use of one of its stoves as “a pleasure and not a bother”, but only if housewives know how to operate it. While the manufacturer designed stoves according to scientific principles to ensure that all requirements for hygiene, efficiency, and usability were met, the housewife was responsible for guaranteeing that the stove satisfied these criteria in practice. Thus, housewives had to acquire the necessary knowledge, by studying the user manual and following strictly the instructions that additionally included the use of the right fuels.106 Likewise, in 1894, the grocer and fuel retailer Aldinger-Weber & Co. in St. Gall promoted specific coal types for different heating systems as well as for specific purposes. “Belgian cube coal”, for instance, was advertised as “excellent for coke stoves or hearths with grates”, “washed cube coal from the Ruhr region” as “low fuming, for steam engines, furnaces, and hearths”, “Anthracite from Belgium and England” as “[…] designated for the use in American stoves”, and “Bärlocher-Kohlen from Augsburg” as “[…] excellent for ironing” (see figure 1).

The housekeeping manual of Coradi-Stahl, however, did not take necessarily such expert recommendations into account but rather reflected the author’s practical experiences. According to her, heating corresponding to her suggestions would have proved to be the best way for controlling the indoor climate. Even if tiled stoves were not suitable for coal, she recommended mixing coal with wood when the room thermometer indicated an insufficient temperature to quickly balance it out. Additionally, Coradi-Stahl did not consider the heat storage capacity of the tiled stove; she suggested operating it continuously, which meant that a certain amount of fuel had to be added from time to time. This contradicted the usual way of operating a tiled stove, which involved lighting a strong fire and then closing the stove’s door to take advantage of the radiant heat. Its continuous operation suggested by Coradi-Stahl simplified temperature control but reduced the stove’s efficiency.107 As her recommendations show, efficiency and thrift did not matter for the author.

As it was shown in this section, health could compete with thrift in the realisation of a healthy indoor climate through heating and ventilation, which was particularly expressed in the housekeeping manual for working-class women. Here, the main goal for heating was to save fuel; healthy or comfortable room temperatures played a subordinate role. It is noteworthy that this housekeeping manual, in contrast to the hygienists’ views, does not locate the realisation of a healthy indoor climate within the sphere of influence or the responsibility of the housewife, but rather relates it to the condition of the chimney and stove. In the housekeeping manual aimed at women managing a middle-class household, on the other hand, rooms were to be heated to a temperature that was within the range defined as healthy by hygienists, regardless of energy use or personal comfort sensation. In addition, a healthy indoor climate was to be realized through the activities of the housewife, i.e. it was her responsibility.

Back to topConclusions

In the second half of the 19th century, domestic hygiene envisioned and defined an ideal indoor climate and endowed it with healthy properties so that the “idea of comfort adopted a new therapeutic nuance”, as Prieto phrased it in 2016.108 This new nuance contrasted the common notion of controlling the indoor climate – the cheapest possible heating of a room to feel more or less comfortable– at least for some time.

According to the values of the hygiene movement and the scientific knowledge of the time, the characteristics of a healthy indoor climate, such as air purity, a certain temperature range, which, however, differed from region to region, and humidity, could be achieved by using suitable stoves, such as the tiled stove in Switzerland, but above all by ventilation. Although indoor climate depends heavily on the buildings themselves, on energy used, and on the technologies available to control it, hygienists considered it a question of individual behaviour, of good and bad habits, and thus a personal responsibility. In this context, hygienists introduced healthy indoor climate, and air purity in particular, as a social norm that was to be followed by the entire population for the sake of health. They identified healthy room climate in cultivated middle-class households as the ideal that should also find its way into working-class and peasant homes.

The medicalisation of the domestic sphere by the hygiene movement was disseminated by domestic science education to all social classes and put more pressure on women to promote health as an ultimate service for the wellbeing of their families.109 In the household, health met another value, namely thrift, which was of paramount importance among the poor. Here, instructions on heating focused on fuel savings, while health was conceived as a value subordinated to thrift that depended on a well-functioning and clean stove and chimney. In the middle-class home, health was at the core of the recommendations for heating, with the housewife in charge of the corresponding “proper” room climate. In this context, there was a strong emphasis on self-responsibility.

It can be assumed that the widespread implementation of the hygienists’ vision of a healthy indoor climate failed at first, as indoor climate was finally controlled by ordinary people and not by experts for hygiene. Nevertheless, the concept of room climate as being important to human health had some long-term consequences. It was the basis of and contributed significantly to the globally effective standardisation of indoor climate and to the institutionalisation of building physics as well as heating and ventilation technology as sciences. In addition, it led to a new awareness of healthy living and comfort. In this context, thermal comfort, of which indoor climate is the most essential component, became a topic to be researched especially in the 20th century.110 This turn towards thermal comfort was also to become evident in the first decades of the 20th century in “new forms of urban development” and “new forms of housing that reconcile the functional imperatives of a modern metropolis with the new health requirements”111, as well as in residential buildings themselves. Technical devices, such as central heating (and air-conditioning in the US112) contributed to domestic hygiene and bodily comfort, initially above all in the wealthier, middle-class households.113 Ultimately, the medicalisation of indoor climate as an “invisible energy policy”114 led to high energy consumption for heating and cooling buildings in Europe and corresponding increasing greenhouse gas emissions from the second half of the 20th century onwards.115

In view of global climate change, Swiss energy policy, similar to the hygiene movement concerning health, relies on personal responsibility116 to promote energy-saving behaviour. This includes “proper” heating and ventilation, for which the Federal Office of Energy provides instructions.117

As this essay has shown, both the idea of personal responsibility and instructions on the proper management of the indoor climate (i.e. heating and ventilation) have a long tradition dating back to the end of the 19th century. But their central motivation shifted from personal health and thrift to global concerns such as global climate change and energy scarcity.

- 1. J. Rogelj et al., “Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5 C in the Context of Sustainable Development”, in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed.), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty: Special Report (Geneva: IPCC, 2018), 141–142, H. de Coninck et al., “Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response”, in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed.), Global Warming, 362–369.

- 2. Nowadays, amid the Covid 19 pandemic, indoor climate and ventilation are again seen as important for health (e.g. Nehul Agarwal et al., “Indoor Air Quality Improvement in COVID-19 Pandemic: Review”, Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 70, 2021).

- 3. Magdalena Daniel, “Haustechnik im 19. Jahrhundert: Das Beispiel der Heizungs- und Ventilationstechnik im Krankenhausbau” (Dissertation, ETH Zürich, Zürich, 2015).

- 4. Beatrix Mesmer, “Reinheit und Reinlichkeit: Bemerkungen zur Durchsetzung der häuslichen Hygiene in der Schweiz”, in Nicolai Bernard and Quirinus Reichen (eds.), Gesellschaft und Gesellschaften: Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Ulrich Im Hof (Bern: Wyss, 1982).

- 5. Ibid., 473–474.

- 6. See also Marsha Ackermann, Cool Comfort: America's Romance with Air-Conditioning (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002), Rune Svarverud, “Ventilation for the Nation: Fresh Air, Sunshine, and the Warfare on Germs in China's National Quest for Hygienic Modernity, 1849-1949”, Environment and History, vol. 26, n°3, 2020.

- 7. Witold Rybczynski, Verlust der Behaglichkeit. Wohnkultur im Wandel der Zeit (München: Dt. Taschenbuch-Verlag), 144–158.

- 8. Vladimir Janković, Confronting the Climate: British Airs and the Making of Environmental Medicine (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

- 9. Gail Cooper, Air-Conditioning America: Engineers and the Controlled Environment, 1900 - 1960 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

- 10. For a social science approach to this concept see Heather Chappells and Elizabeth Shove, “Debating the Future of Comfort: Environmental Sustainability, Energy Consumption and the Indoor Environment”, Building Research & Information I, vol. 33, n° 1, 2005.

- 11. The history of heating in Switzerland is best reflected in a company history: Peter Brügger and Guido Irion, Wie die Heizung Karriere machte: Technik, Geschichte, Kultur. 150 Jahre Sulzer-Heizungstechnik (Winterthur: Sulzer Infra, 1991). Additionally, the dissertation project of the author deals with heating in Switzerland from the 19th to the end of the 20th century. Barbara Koller investigated indoor air in terms of its importance for the development of housing inspections and housing standards (Barbara Koller, “"Wo gute Luft und schlechte Luft sich scheiden": Die Entwicklung hygienischer Wohnstandards und deren sozialpolitische Brisanz Ende des 19. und zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts”, in Robert Jütte (ed.), Medizin, Gesellschaft und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung, vol. 14, Berichtsjahr 1995 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1996) and Jon Mathieu analysed the medical and public discourses on ventilation and pointed out that this new and unfamiliar means of improving health was met with scepticism in Swiss Society (Jon Mathieu, “Das offene Fenster: Überlegungen zu Gesundheit und Gesellschaft im 19. Jahrhundert”, Annales da la Societad Retorumantscha, vol. 106, 1993.

- 12. Sarah Royston, Jan Selby, and Elizabeth Shove, “Invisible Energy Policies: A New Agenda for Energy Demand Reduction”, Energy Policy, vol. 123, 2018.

- 13. As recent research has shown, social norms are impacting energy consumption. Jon M. Jachimowicz, “Three Thumbs up for Social Norms”, Nature Energy, vol. 5, n° 11, 2020.

- 14. Janković, Confronting, 6 (cf. note 8).

- 15. Philipp Sarasin, Reizbare Maschinen: Eine Geschichte des Körpers 1765 - 1914, 4th ed. (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2016 (2001)), 33–51, Mesmer Beatrix (ed.), Die Verwissenschaftlichung des Alltags: Anweisungen zum richtigen Umgang mit dem Körper in der schweizerischen Populärpresse ; 1850 - 1900 (Zürich: Chronos, 1997).

- 16. Susanne Breuss, “Die Stadt, der Staub und die Hausfrau: Vom Verhältnis schmutziger Stadt und sauberem Heim”, in Olaf Bockhorn et al. (eds.), Urbane Welten: Referate der Österreichischen Volkskundetagung 1998 in Linz (Wien: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Volkskunde, 1999), Simona Isler, Politiken der Arbeit: Perspektiven der Frauenbewegung um 1900 (Basel: Schwabe, 2019), 104, Mesmer, “Reinheit” (cf. note 4).

- 17. The textbooks on hygiene were written by experts, e.g. Swiss and German physicians, like Jakob Laurenz Sonderegger (1825–1896), Carl Flügge (1847–1923), specialists for hygiene from other fields like architecture as Adolph Wolpert (1832–1907), or natural scientists with a special interest in hygiene (Max von Pettenkofer, 1818–1901). All of them practiced in the late 19th century and had scientific and/or public reputation.

- 18. Verband für Soziale Kultur, Das häusliche Glück: Vollständiger Haushaltungsunterricht nebst Anleitung zum Kochen für Arbeiterfrauen, zugleich ein nützliches Hülfsbuch für alle Frauen und Mädchen, die "billig und gut" haushalten lernen wollen, 10th ed., herausgegeben von einer Commssion des Verbandes "Arbeiterwohl" (Mönchengladbach, Leipzig: Riffart, 1882).

- 19. Franz Josef Stegmann and Peter Langhorst, “Geschichte der sozialen Ideen im deutschen Katholizismus”, in Helga Grebing (ed.), Geschichte der sozialen Ideen in Deutschland: Sozialismus - katholische Soziallehre - protestantische Sozialethik ; ein Handbuch, 2nd ed. (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2005), 661.

- 20. Brenner, “Aufforderung zur Gründung weiblicher Fortbildungsschulen”, Die gewerbliche Fortbildungsschule: Blätter zur Förderung der Interessen derselben in der Schweiz, vol. 3, 10-11, 1887, 77, o. A., “Der Klerus und die Soziale Frage”, Schweizerische Kirchenzeitung : Fachzeitschrift für Theologie und Seelsorge, n°44, 1882, 348.

- 21. o. A., “Jugendschriften”, Schweizerische Kirchenzeitung : Fachzeitschrift für Theologie und Seelsorge, n°51, 1892, 404.

- 22. Emma Coradi-Stahl, Wie Gritli haushalten lernt: Eine Anleitung zur Führung eines bürgerlichen Haushalts in zehn Kapiteln (Zürich: 1902). Coradi-Stahl was engaged in women’s education as a housekeeping-teacher and an advisor for schools. She authored several books on household management and was founder and editor of the women's magazine "Schweizer Frauenheim". The individual chapters of “Gritli” were originally published in this magazine in the late 1890s and re-published as a book in 1902. Regina Ludi, “Emma Coradi-Stahl: e-HLS”, Mar. 4, 2004, hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/009286/2004-03-04/ (accessed Feb 13, 2022).

- 23. Id.

- 24. Compared to the large European cities, such as London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna, however, the Swiss cities were small. Zurich had only about 150,703 inhabitants in 1900, and Basel 109,161 (Historische Statistik der Schweiz - Online Ausgabe, hsso.ch/, Table B37).

- 25. Georg Kreis, Der Weg zur Gegenwart: Die Schweiz im neunzehnten Jahrhundert (Basel: Birkhäuser, 1986), 185, Philipp Sarasin, “Stadtgeschichte der modernen Schweiz”, in Georg Kreis (ed.), Die Geschichte der Schweiz (Basel: Schwabe, 2014), 611–613.

- 26. Kreis, Der Weg, 189 (cf. note 25), Daniel Künzle, “Stadtwachstum, Quartierbildung und soziale Konflikte am Beispiel von Zürich-Aussersihl 1850-1914”, in Sebastian Brändli et al. (eds.), Schweiz im Wandel: Studien zur neueren Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Festschrift für Rudolf Braun zum 60. Geburtstag (Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1990), 47, Albert Petermann, “Die Wohnungsausstattung”, in Schweizerischer Hauseigentümerverband (ed.), 50 Jahre Schweizerische Wohnwirtschaft: Jubiläumsschrift zum 50 jährigen Bestehen des Schweizerischen Hauseigentümerverbands (Zürich: 1964), 145–148.

- 27. id., Carl Landolt, Die Wohnungs-Enquête in der Stadt Bern vom 17. Februar bis 11. März 1896 (Bern: Neukomm & Zimmermann, 1899), 690–691, Philipp Sarasin, Stadt der Bürger: Struktureller Wandel und bürgerliche Lebenswelt Basel 1870-1900 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1997), 45–61 Künzle, “Stadtwachstum,”40–54 (cf. note 26), Hans-Peter Bärtschi, “Die Lebensverhältnisse der Schweizer Arbeiter um 1900”, Gewerkschaftliche Rundschau : Vierteljahresschrift des Schweizerischen Gewerkschaftsbundes vol. 75, n°4, 1983.

- 28. E.g Jakob Laurenz Sonderegger, Vorposten der Gesundheitspflege oder der Kampf um's Dasein des Einzelnen und ganzer Völker (Berlin: Verlag von Hermann Peters, 1873).

- 29. Künzle, “Stadtwachstum” (cf. note 26).

- 30. E.g. Christopher Hamlin, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick: Britain, 1800 - 1854, Cambridge history of medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- 31. E.g. Anne Hardy, The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine, 1856 - 1900 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003), Davide Rodogno, Bernhard Struck, and Jakob Vogel (eds.), Shaping the Transnational Sphere: Experts, Networks and Issues from the 1840s to the 1930s, v.14 of Contemporary European History (New York, NY: Berghahn Books, 2014), Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantiküberquerungen: Die Politik der Sozialreform, 1870 - 1945, vol. 40 of Transatlantische historische Studien (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2010), Biswamoy Pati, and Mark Harrison (eds.), Society, Medicine and Politics in Colonial India, 1st ed., The Social History of Health and Medicine in South Asia (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), Alison Bashford, Imperial Hygiene: A Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health (Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

- 32. Philipp Sarasin, “Die Geschichte der Gesundheitsvorsorge: Das Verhältnis von Selbstsorge und staatlicher Intervention im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert”, Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 14, n° 2, 2011, 42–44.

- 33. Sarasin, Maschinen, 33–51 (cf. note 15).

- 34. Mesmer, “Reinheit,” (cf. note 4).

- 35. Adolph Wolpert, Theorie und Praxis der Ventilation und Heizung: Handbuch der Ventilation und Heizung mit Einschluss der Hilfswissenschaften zum Selbststudium und zum Gebrauch bei Vorlesungen über Wohnungshygiene (Leipzig: Baumgärtner, 1887), 33.

- 36. Ibid., 33–35.

- 37. E.g. Pettenkofer’s article series on the impact of stoves and air heating systems on indoor air quality, published in the early 1850’s( Max v. Pettenkofer, “Ueber den Unterschied zwischen Luftheizung und Ofenheizung in ihrer Einwirkung auf die Zusammensetzung der Luft der beheizten Räume”, Polytechnisches Journal vol. 119, X, 1851, Pettenkofer, “Ueber den Unterschied zwischen Luftheizung und Ofenheizung in ihrer Entwicklung auf die Zusammensetzung der Luft der beheizten Räume: (Fortsetzung von S. 51 dieses Bandes)”, Polytechnisches Journal vol. 1851, L.III, 119, Pettenkofer, “Ueber den Unterschied zwischen Luftheizung und Ofenheizung in ihrer Einwirkung auf die Zusammensetzung der Luft der beheizten Räume: (Schluß von Bd. CXIX S. 290.)”, Polytechnisches Journal vol. 120, XCI, 1851.

- 38. E.g. Max von Pettenkofer, Bericht über die Ventilationsapparate, in: Pettenkofer, Über den Luftwechsel in Wohngebäuden (München: Cotta, 1858), 19–68, o. A., “Königreich Sachsen (Schulhygienische Statistik)”, Schweizerisches Schularchiv vol. 3, n. 5, 1882, Schweizerische Polytechnische Zeitschrift, “Ueber das angebliche Austrocknen der Luft in Räumen, die durch Centralluftheizungsapparate erwärmt werden, und über das Mass des Luftwechsels in solchen Lokalitäten”, vol. 13, n° 2, 1868, Daniel, “Haustechnik” (cf. note 3).

- 39. Sarasin, Maschinen (cf. note 15).

- 40. Wolfgang U. Eckart, Geschichte, Theorie und Ethik der Medizin, 8th ed., Springer-Lehrbuch (Berlin: Springer, 2017), 11–17.

- 41. Sarasin, Maschinen, esp. 51–71 (cf. note 15), Sarasin, “The Body as Medium: Nineteenth-Century European Hygiene Discourse”, Grey Room vol. 29, 2007, Janković, Confronting, 18–21 (cf. note 8).

- 42. Sarasin, Maschinen, 33–51 (cf. note 15).

- 43. E.g. Max v. Pettenkofer, Beziehungen der Luft zu Kleidung, Wohnen, Boden: Drei populäre Vorlesungen. Gehalten im Albert-Verein zu Dresden am 21., 23. und 25. März 1872 (Braunschweig: Friedr. Vieweg und Sohn, 1872), S. 56–57. On different concepts of air purity see also Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination (Leamington Spa: Berg, 1986), (France), Janković, Confronting, (Victorian Britain) (cf. note 8), Svarverud, “Ventilation,” (China) (cf. note 6).

- 44. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 43 (cf. note 28) See also Mathieu, “Fenster”, 295–296 (cf. note 11).

- 45. Jan Sundell, “On the History of Indoor Air Quality and Health”, Indoor Air vol. 14, n°7, 2004, 52, David Hansen, Indoor Air Quality Issues (Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis, 2000), 4–5.

- 46. Max von Pettenkofer, Bericht über die Ventilationsapparate, in: Pettenkofer, Luftwechsel, 23 (cf. note 38).

- 47. Ibid., The Swiss Physician Sonderegger popularized von Pettenkofer’s ventilation rate in Switzerland (Sonderegger, Vorposten, 52– 53 (cf. note 28)). Quite similar average ventilations rates were recommended by French, British, and American hygienists (Arthur Jules Morin, Salubrité des habitations: manuel pratique du chauffage et de la ventilation (Paris: 1868), 38. Morin's ventilation rates, however, were applied to a wide variety of buildings such as schools, hospitals, barracks and prisons, taking into account the characteristics of the people who lived in them (Morin, “On the Ventilation of Public Buildings”, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers vol. 18, n° 1, 1867, Rybczynski, Verlust, 153 (cf. note 7), John E. Janssen, “The History of Ventilation and Air Temperature Control”, ASHRAE Journal, September 1999, 48–51).

- 48. e.g. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 16–18 (cf. note 28).

- 49. Priscilla J. Brewer, From Fireplace to Cookstove: Technology and the Domestic Ideal in America (Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse Univ. Press, 2000), 18–25, Rybczynski, Verlust, 150–151 (cf. note 7), Sean Patrick Adams, Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the Nineteenth Century, How things worked (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2014), 24, Emmanuelle Gallo, “Lessons Drawn from the History of Heating: A French Perspective”, in Mogens Rudiger (ed.), The Culture of Energy (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 273.

- 50. E.g. Rybczynski, Verlust, 156–157 (cf. note 7), Gallo, “Lessons”, 173 (cf. note 49), Adams, Home Fires, 94–104 (cf. note 49). See also Annik Pardailhé-Galabrun, The Birth of Intimacy: Privacy and Domestic Life in Early Modern Paris (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991), 120–22, Joan E. DeJean, The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual-and the Modern Home Began, (e-Book) (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010), 95–96, Benjamin Franklin, “Beschreibung neuer Pensylvanischer Stubenwärmer”, in Benjamin Franklin (ed.), Sämmtliche Werke. Zweiter Band: Übersetzt von Gottfried Traugott Wenzel (Dresden: Waltherische Hofbuchhandlung, 1780), 123- 124.

- 51. Johann Jacob Volkmann, Neueste Reisen durch Frankreich: vorzüglich in Absicht auf die Naturgeschichte, Oekonomie, Manufakturen und Werke der Kunst aus den besten Nachrichten und neuern Schriften zusammengetragen (Leipzig: Fritsch, 1787/1788), 176–177, Samuel Engel, “Abhandlung von dem aller Orten eingerissenen Holzmangel, dessen Ursachen, und denen dagegen dienlichen Mitteln, denen von Pflanzung und Besorgung der wilden Bäume”, Der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft in Bern Sammlungen von landwirthschaftlichen Dingen, n° 3, 1760, 53, Sonderegger, Vorposten, 54 (cf. note 28).

- 52. Krünitz Encyklopädie, “Ofen”, in Krünitz, Johann Georg et al. (ed.), Johann Georg Krünitz ökonomisch-technologische Encyklopädie, oder allgemeines System der Staats-, Stadt-, Haus- und Landwirthschaft, und der Kunst-Geschichte, in alphabetischer Ordnung: Universität Trier (2001) http://www.kruenitz1.uni-trier.de/ (Berlin, 1773-1858).

- 53. s.v., “Heizung”, in Meyers Konversationslexikon: (Retrodigitalisiert im Projekt "Retro-Bibliothek" http://www.retrobibliothek.de/), 4th ed. (Leipzig, Wien: Verlag des Bibliografischen Instituts, 1885-1892), S. 335.

- 54. Mathieu, “Fenster”, (cf. note 11).

- 55. e.g. Daniel, “Haustechnik”, (cf. note 3).

- 56. Landolt, Wohnungs-Enquête Bern, 461 (cf. note 27), Statistisches Amt der Stadt Zürich, Statistisches Jahrbuch der Stadt Zürich: Sechster und Siebenter Jahrgang, 1910 und 1911, zum Teil auch 1912 (Zürich: Rascher & Co, 1914), 423.

- 57. Daniel Marek, “Kohle: Die Industrialisierung der Schweiz aus der Energieperspektive 1850-1900” (Dissertation, Universität Bern, Bern, 1992), 123, Petermann, “Wohnungsausstattung”, 150 (cf. note 26).

- 58. Marek, “Kohle”, 108, 126–131 (cf. note 57).

- 59. Mathieu, “Fenster” (cf. note 11).

- 60. In addition, of course, other factors were essential for planning and the design of a heating system (Hermann Rietschel, Leitfaden zum Berechnen und Entwerfen von Lüftungs- und Heizungs-Anlagen: Auf Anregung seiner Excellenz des Herrn Minister der Öffentliche Arbeiten verfasst, 2nd ed. (Berlin: Julius Springer, 1894).

- 61. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 55 (cf. note 28) Jakob Laurenz Sonderegger, and Elias Haffter, Vorposten der Gesundheitspflege, 5th ed. (Berlin: Julius Springer, 1901), 269. See also Wolpert, Theorie und Praxis, 383, 635–639 (cf. note 35), Sonderegger, Vorposten, 55 (cf. note 28).

- 62. Manfred Seifert, Technik–Kultur: Das Beispiel Wohnraumheizung (Dresden: Thelem, 2012), 182.

- 63. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 55 (cf. note 28).

- 64. Id., Wolpert, Theorie und Praxis, 635–639 (cf. note 35), Carl Flügge, Grundriss der Hygiene für, Studirende und praktische Ärzte, Medicinal- und Verwaltungsbeamte, 5th ed. (Leipzig: Veit und Comp, 1902), 383, Sonderegger and Haffter, Vorposten, 1901, 267–273 (cf. note 62).

- 65. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 34 (cf. note 28), Pettenkofer, Beziehungen, 71 (cf. note 43), see also Mathieu, “Fenster”, 295–296 (cf. note 11).

- 66. Idem, Mesmer, “Reinheit”, 481 (cf. note 4), Pettenkofer, Beziehungen, 71 (cf. note 43).

- 67. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 61–68 (cf. note 28), Sonderegger and Haffter, Vorposten, 1901, 261 (cf. note 62), Victor Böhmert, Arbeiterverhältnisse und Fabrikeinrichtungen der Schweiz: Erstattet im Auftrage der Eidgenössischen Generalcommission für die Wiener Weltausstellung, I. Band (Zürich: C. Schmidt, 1873), 415, C. Schwatlo, “Ventilation und Heizung”, Die Eisenbahn vol. 13, n° 19, 1880, 116–117.

- 68. Paul Niemeyer, Aerztlicher Rathgeber für Mütter: Zwanzig Briefe über die Pflege des Kindes von der Geburt bis zur Reife (Stuttgart: Engelhorn, 1877), 114–117, Mathieu, “Fenster”, 297 (cf. note 11).

- 69. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 62 (cf. note 28).

- 70. Petermann, “Wohnungsausstattung”, 145–148 (cf. note 26), Landolt, Wohnungs-Enquête Bern, 690–691 (cf. note 27), Sarasin, Stadt, 45–6 (cf. note 27), Künzle, “Stadtwachstum,”, 50–54 (cf. note 26).

- 71. Id.

- 72. Sonderegger, Vorposten, 23 (cf. note 28).

- 73. Ibid., 62.

- 74. Böhmert, Arbeiterverhältnisse, 415 (cf. note 68).

- 75. Pettenkofer, Luftwechsel, 91–92 (cf. note 38).

- 76. Ibid., 92.

- 77. Sonderegger and Haffter, Vorposten, 1901, 269 (cf. note 62).

- 78. Ibid., 267.

- 79. Breuss, “Stadt” (cf. note 16), Isler, Politiken, 104 (cf. note 16), Mesmer, “Reinheit” (cf. note 4).

- 80. See Juliane Jacobi, Mädchen- und Frauenbildung in Europa: Von 1500 bis zur Gegenwart, 1st ed., (Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2013).

- 81. Anne-Marie Stalder, “Die Erziehung zur Häuslichkeit: Über den Beitrag des hauswirtschaftlichen Unterrichts zur Disziplinierung der Unterschichten im 19. Jahrhundert”, Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte vol. 34, n° 3, 1984, Isler, Politiken (cf. note 16).

- 82. Verband für Soziale Kultur, Häusliches Glück, 38 (cf. note 18).

- 83. Id.

- 84. Stegmann and Langhorst, “Geschichte,” 661 (cf. note 19).

- 85. The feminine traits humility, self-sacrifice and subordination as well as the importance of Christian Values were addressed in a letter from a priest which formed the introduction to “Das Häusliche Glück” (Verband für Soziale Kultur, Häusliches Glück (cf. note 18).

- 86. Ibid., 30.

- 87. Ibid., 23.

- 88. Ibid., 41.

- 89. Ibid., 42.

- 90. Ibid., 41–42.

- 91. Ibid., 40.

- 92. Ibid., 42.

- 93. Id.

- 94. Ibid., 40

- 95. Ibid., 38–39.

- 96. Ibid., 23–24.

- 97. Coradi-Stahl, Wie Gritli, 46 (cf. note 22).

- 98. Id.

- 99. Ibid., 47.

- 100. Id.

- 101. Ibid, 50.

- 102. Id.

- 103. E.g. Rietschel, Leitfaden, 106 (cf. note 60), o. A., “Die Ökonomie der häuslichen Heizung: Nach dem Rathaus-Vortrag vom 18. Januar 1906, gehalten von Prof. Dr. E. J. Constam in Zürich”, Schweizerische Bauzeitung vol. 47, n° 11, 1906, Joh. Eugen Mayer, “Sachgemäße Beheizung unserer Wohnräume”, Illustrierte schweizerische Handwerker-Zeitung vol. 30, n° 34, 1914.

- 104. e.g. Zuger Volksblatt, “Der Junker & Ruh-Ofen: Advertorial”, Oct. 8, 1890, 128–134, C. Baerlocher, “Vom Heizen”, Wohnen vol. 2, n° 11, 1927.

- 105. o. A., “Ökonomie der häuslichen Heizung” (cf. note 104).

- 106. “Junker & Ruh Ofen, Advertorial 1890” (cf. note 105).

- 107. Coradi-Stahl, Wie Gritli, 47 (cf. note 22).

- 108. Eduardo Prieto, “The Welfare Cultures: Poetics of Comfort in the Architecture of the 19th and 20th Centuries”, in Franz Graf and Giulia Marino (eds.), Building Environment and Interior Comfort in 20th Century Architecture: Understanding Issues and Developing Conservation Strategies (Lausanne: Presses Polytechniqes et Universitaires Romandes, 2016), 62.

- 109. Ruth Cowan Schwartz, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Heart to the Microwave, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1983), Joel Mokyr, “Why ‘More Work for Mother?’: Knowledge and Household Behavior, 1870-1945”, The Journal of Economic History vol. 60, n° 1, 2000.

- 110. E.g. Janssen, “History” (cf. note 47) Jos Tomlow, “Bauphysik und die technische Literatur des Neuen Bauens”, Bauphysik vol. 29, n° 2, 2007.

- 111. Dieter Schott, Europäische Urbanisierung (1000 - 2000): Eine umwelthistorische Einführung (Köln: Böhlau, 2014), 278.

- 112. Ackermann, Cool Comfort (cf. note 6).

- 113. Katrin Eberhard, Maschinen zuhause: Die Technisierung des Wohnens in der Moderne, 1st ed., Architektonisches Wissen (Zürich: gta Verlag, 2011).

- 114. Royston, Selby, and Shove, “Invisible,” (cf. note 12).

- 115. E.g. Oswaldo Lucon et al., “Buildings”, in Ottmar et al. Edenhofer (ed.), Climate change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III contribution to the Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 116. Anna Suppa et al., Zusammenhang zwischen Einkommens- und Energiearmut sowie die Folgen energetischer Sanierungen für vulnerable Gruppen. Eine qualitative Analyse (Grenchen: Bundesamt für Wohnungswesen, 2019), 54–55.

- 117. Energiefachstellen der Kantone and EnergieSchweiz, Komfortabler Wohnen – alles rund ums Heizen und Lüften (Bern: 2016).

Ackermann Marsha, Cool Comfort: America’s Romance with Air-Conditioning (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002).

Adams Sean Patrick, Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the Nineteenth Century, How things worked (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2014).

Agarwal Nehul et al., “Indoor Air Quality Improvement in COVID-19 Pandemic: Review”, Sustainable Cities and Society vol. 70, 2021, 102942.

Baerlocher C., “Vom Heizen”, Wohnen vol. 2, n° 11, 1927, 291–292.

Bärtschi Hans-Peter, “Die Lebensverhältnisse der Schweizer Arbeiter um 1900”, Gewerkschaftliche Rundschau : Vierteljahresschrift des Schweizerischen Gewerkschaftsbundes vol. 75, n° 4, 1983, 118–124.

Bashford Alison, Imperial Hygiene: A Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health (Houndsmills [England]1: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Nicolai Bernard, Reichen Quirinus (eds.), Gesellschaft und Gesellschaften: Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Ulrich Im Hof (Bern: Wyss, 1982).

Bockhorn Olaf et al. (eds.), Urbane Welten: Referate der Österreichischen Volkskundetagung 1998 in Linz (Wien: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Volkskunde, 1999).

Böhmert Victor, Arbeiterverhältnisse und Fabrikeinrichtungen der Schweiz: Erstattet im Auftrage der Eidgenössischen Generalcommission für die Wiener Weltausstellung, I. Band (Zürich: C. Schmidt, 1873).

Brändli Sebastian et al. (eds.), Schweiz im Wandel: Studien zur neueren Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Festschrift für Rudolf Braun zum 60. Geburtstag (Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1990).

Brenner, “Aufforderung zur Gründung weiblicher Fortbildungsschulen”, Die gewerbliche Fortbildungsschule: Blätter zur Förderung der Interessen derselben in der Schweiz vol. 3, 10-11, 1887, 73–78.

Breuss Susanne, “Die Stadt, der Staub und die Hausfrau: Vom Verhältnis schmutziger Stadt und sauberem Heim”, in Olaf Bockhorn et al. (eds.), Urbane Welten: Referate der Österreichischen Volkskundetagung 1998 in Linz (Wien: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Volkskunde, 1999), 353–76.

Brewer Priscilla J. B., From Fireplace to Cookstove: Technology and the Domestic Ideal in America (Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse Univ. Press, 2000).

Brügger Peter, Irion Guido, Wie die Heizung Karriere machte: Technik, Geschichte, Kultur. 150 Jahre Sulzer-Heizungstechnik. (Winterthur: Sulzer Infra, 1991).

Chappells Heather, Shove Elizabeth, “Debating the Future of Comfort: Environmental Sustainability, Energy Consumption and the Indoor Environment”, Building Research & Information vol. 33, n° 1, 2005, 32–40.

de Coninck Heleen et al., “Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response”, in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed.), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening

de Coninck Heleen et al., the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty: Special Report (Geneva: IPCC, 2018), 315–443.

Cooper Gail, Air-Conditioning America: Engineers and the Controlled Environment, 1900 - 1960 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2002).

Coradi-Stahl Emma, Wie Gritli haushalten lernt: Eine Anleitung zur Führung eines bürgerlichen Haushalts in zehn Kapiteln (Zürich: 1902).

Corbin Alain, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination (Leamington Spa: Berg, 1986).

Cowan Schwartz Ruth, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Heart to the Microwave, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

Daniel Magdalena, “Haustechnik im 19. Jahrhundert: Das Beispiel der Heizungs- und Ventilationstechnik im Krankenhausbau” (Dissertation, ETH Zürich, Zürich, 2015).

DeJean Joan E., The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual-and the Modern Home Began, (e-Book) (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010).

DeJean Joan E., “Der Junker & Ruh-Ofen: Advertorial”, Zuger Volksblatt, Oct. 8, 1890, 3.

DeJean Joan E., “Der Klerus und die Soziale Frage”, Schweizerische Kirchenzeitung : Fachzeitschrift für Theologie und Seelsorge, n° 44, 1882, 347–349.

DeJean Joan E., “Die Ökonomie der häuslichen Heizung: Nach dem Rathaus-Vortrag vom 18. Januar 1906, gehalten von Prof. Dr. E. J. Constam in Zürich”, Schweizerische Bauzeitung vol. 47, n° 11, 1906, 128–134.

Eberhard Katrin, Maschinen zuhause: Die Technisierung des Wohnens in der Moderne, 1st ed., Architektonisches Wissen (Zürich: gta Verlag, 2011).

Eckert Wolfgang U., Geschichte, Theorie und Ethik der Medizin, 8th ed., Springer-Lehrbuch (Eckart Berlin: Springer, 2017).

Edenhofer Ottmar et al. (ed.), Climate change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III contribution to the Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Eibach Joachim and Schmidt-Voges Inken (eds.), Das Haus in der Geschichte Europas (Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015).

Energiefachstellen der Kantone, EnergieSchweiz, Komfortabler Wohnen – alles rund ums Heizen und Lüften (Bern: 2016).

Engel Samuel, “Abhandlung von dem aller Orten eingerissenen Holzmangel, dessen Ursachen, und denen dagegen dienlichen Mitteln, denen von Pflanzung und Besorgung der wilden Bäume”, Der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft in Bern Sammlungen von landwirthschaftlichen Dingen, n° 3, 1760, 524–597.

Flügge Carl, Grundriss der Hygiene: für Studirende und praktische Ärzte, Medicinal- und Verwaltungsbeamte, 5th ed. (Leipzig: Veit und Comp, 1902).

Franklin Benjamin, “Beschreibung neuer Pensylvanischer Stubenwärmer”, in Benjamin Franklin (ed.), Sämmtliche Werke. Zweiter Band: Übersetzt von Gottfried Traugott Wenzel (Dresden: Waltherische Hofbuchhandlung, 1780), 108–58.

Franklin Benjamin (ed.), Sämmtliche Werke. Zweiter Band: Übersetzt von Gottfried Traugott Wenzel (Dresden: Waltherische Hofbuchhandlung, 1780).

Gallo Emmanuelle, “Lessons Drawn from the History of Heating: A French Perspective”, in Mogens Rudiger (ed.), The Culture of Energy (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 268–80.

Gessetzessammlung des Kantons Basel-Stadt, “SG 370.100 - Wohnungsgesetz vom 18. April 1907 (Stand 1. Januar 2007)”, www.gesetzessammlung.bs.ch/app/de/texts_of_law/370.100/versions/3666 (accessed Feb. 13, 2022).

Graf Franz, Marino Giulia (eds.) , Building Environment and Interior Comfort in 20th Century Architecture: Understanding Issues and Developing Conservation Strategies (Lausanne: Presses Polytechniqes et Universitaires Romandes, 2016).

Grebing Helga (ed.), Geschichte der sozialen Ideen in Deutschland: Sozialismus - katholische Soziallehre - protestantische Sozialethik ; ein Handbuch, 2nd ed. (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2005).

Hamlin Christopher, Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick: Britain, 1800 - 1854, Cambridge history of medicine (Cambridge1: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Hansen David, Indoor Air Quality Issues (Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis, 2000).

Hardy Anne, The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine, 1856 - 1900 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003).

Historische Statistik der Schweiz - Online Ausgabe, hsso.ch/.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed.), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty: Special Report (Geneva: IPCC, 2018).

Isler Simona, Politiken der Arbeit: Perspektiven der Frauenbewegung um 1900 (Basel: Schwabe, 2019).

Jachimowicz Jon M., “Three Thumbs up for Social Norms”, Nature Energy vol. 5, n° 11, 2020, 826–827.

Jacobi Juliane, Mädchen- und Frauenbildung in Europa: Von 1500 bis zur Gegenwart, 1st ed. (Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2013).

Janković Vladimir, Confronting the Climate: British Airs and the Making of Environmental Medicine, 1st ed. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Janssen John E., “The History of Ventilation and Air Temperature Control”, ASHRAE Journal, September 1999, 1999, 47–52.

Joris Elisabeth, “Die Schweizer Hausfrau: Genese eines Mythos”, in Sebastian Brändli et al. (eds.), Schweiz im Wandel: Studien zur neueren Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Festschrift für Rudolf Braun zum 60. Geburtstag (Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1990), 99–116.

Joris Elisabeth, “Jugendschriften” Schweizerische Kirchenzeitung : Fachzeitschrift für Theologie und Seelsorge, n° 51, 1892, 404–405.

Jütte Robert (ed.), Medizin, Gesellschaft und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung, vol. 14, Berichtsjahr 1995 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1996).

Koller Barbara, “‘Wo gute Luft und schlechte Luft sich scheiden’: Die Entwicklung hygienischer Wohnstandards und deren sozialpolitische Brisanz Ende des 19. und zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts”, in Robert Jütte (ed.), Medizin, Gesellschaft und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung, vol. 14, Berichtsjahr 1995 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1996), 121–42.

Kreis Georg, Der Weg zur Gegenwart: Die Schweiz im neunzehnten Jahrhundert (Basel: Birkhäuser, 1986).

Kreis Georg (ed.), Die Geschichte der Schweiz (Basel: Schwabe, 2014).

Kreis Georg (ed.), “Königreich Sachsen (Schulhygienische Statistik)”, Schweizerisches Schularchiv vol. 3, n° 5, 1882, 130–131.

Krünitz Encyklopädie, “Ofen”, in Johann Georg Krünitz, et al. (ed.), Johann Georg Krünitz ökonomisch-technologische Encyklopädie, oder allgemeines System der Staats-, Stadt-, Haus- und Landwirthschaft, und der Kunst-Geschichte, in alphabetischer Ordnung: Universität Trier (2001) http://www.kruenitz1.uni-trier.de/ (Berlin1773-1858), 71–373.

Künzle Daniel, “Stadtwachstum, Quartierbildung und soziale Konflikte am Beispiel von Zürich-Aussersihl 1850-1914”, in Sebastian Brändli et al. (eds.), Schweiz im Wandel: Studien zur neueren Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Festschrift für Rudolf Braun zum 60. Geburtstag (Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1990), 43–58.

Landolt Carl, Die Wohnungs-Enquête in der Stadt Bern vom 17. Februar bis 11. März 1896 (Bern: Neukomm & Zimmermann, 1899).

Lucon Oswaldo et al., “Buildings”, in Ottmar Edenhofer, et al. (ed.), Climate change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III contribution to the Fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 671–738.

Ludi Regina, “Emma Coradi-Stahl: e-HLS”, Mar. 4, 2004, hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/009286/2004-03-04 (accessed Feb 13, 2022).

Marek Daniel, “Kohle: Die Industrialisierung der Schweiz aus der Energieperspektive 1850-1900” (Dissertation, Universität Bern, Bern, 1992).

Mathieu Jon, “Das offene Fenster: Überlegungen zu Gesundheit und Gesellschaft im 19. Jahrhundert”, Annales da la Societad Retorumantscha vol. 106, 1993, 291–306.

Mayer Joh. Eugen, “Sachgemäße Beheizung unserer Wohnräume”, Illustrierte schweizerische Handwerker-Zeitung vol. 30, n° 34, 1914, 523–524.

Mesmer Beatrix, “Reinheit und Reinlichkeit: Bemerkungen zur Durchsetzung der häuslichen Hygiene in der Schweiz”, in Nicolai Bernard and Quirinus Reichen (eds.), Gesellschaft und Gesellschaften: Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Ulrich Im Hof (Bern: Wyss, 1982), 470–94.

Mesmer Beatrix (ed.), Die Verwissenschaftlichung des Alltags: Anweisungen zum richtigen Umgang mit dem Körper in der schweizerischen Populärpresse ; 1850 - 1900 (Zürich: Chronos, 1997).