Networks of power? Rethinking class, gender and entrepreneurship in English electrification, 1880-1924

School of Philosophy, Religion and the History of Science, University of Leeds, UK.

g.j.n.gooday[at]leeds.ac.uk

School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies, University of Leeds, UK.

a.l.moore[at]leeds.ac.uk

Traditional energy histories have treated electrification as an inevitability: the assumption has been that making cheap energy supply readily available for the masses required the energy efficiency uniquely attainable by large-scale networked electricity grids. While our account does not question that assumption, such a rationale can only explain the onset of electrification for contexts in which large scale electricity grids are already accessible to all. It cannot explain the earliest phase of electrification: what motivated the take up of electricity before such grids and their attendant economics actually existed to make it affordable and indeed competitive? We focus on the case of England before its National Grid was launched in 1926, a time when such alternatives as coal or its by-product coal-gas offered energy in a form that was cheaper or more convenient than stand-alone electrical installations and highly localised electricity infrastructures. Our initial aim is to survey a range of cultural rather than technocratic reasons for the early take-up of electricity in the 1880s to 1890s, treating it then as a luxury rather than a commonplace utility. In doing so, we return to Thomas Hughes’ seminal Networks of Power (1983) to examine how far the growth of electrical power supply was shaped not just by engineers and politicians that predominate in his account, but by old-money inherited aristocracy that Hughes touches upon only briefly. Specifically we investigate how the nascent electrical industry looked to these powerful wealthy aristocratic technophiles, male and female, to serve as ‘influencers’ to help broaden the appeal of domestic electricity as essential to a desirable life-style of glamorous modernity.

Plan de l'article

- Introduction: Challenging the ‘inevitable’ in pre-grid energy history; Histories of Cultural Persuaders and their Homes

- Revisiting Hughesian historiography

- The electric culture of the celebrity aristocrat client and middle-class emulation

- Aristocratic and Middle-class Role Models of Women Shaping the Home

- Women of Power in Electrification

- The country house as a strategic site of patronage and electrical display

- Conclusion: mapping the networks of symbiosis

Introduction: Challenging the ‘inevitable’ in pre-grid energy history; Histories of Cultural Persuaders and their Homes

Traditional energy histories have tended to treat electrification as an inevitable feature of industrial modernization, (over-)determined by economic imperatives for energy efficiency. Such accounts routinely invoke the significant economies of scale achievable by large-scale electricity distribution networks as a key factor in rendering electrical supply affordable to the majority of consumers.1 But this reliance on rationalist economic explanations is somewhat misleading - while a necessary part of the explanation, it is insufficient. Economic explanations only work to explain electrification once a (nascent) National Grid already exists to supply it cheaply enough via a national network infrastructure. How then can we explain the take-up of electricity before such an affordable supply was actually available?

For this paper, we focus on this scenario for the case of England prior to the launch of its National Grid in 1926 –and its nationalisation as part of the Welfare State by the UK’s Labour government in 1948.2 The crucial (and previously unasked) question about the Grid is therefore not so much: at what point in the development of the Grid did the cost of electrical energy become competitive with that of its older rivals? Rather one might ask: given its prior unaffordability to the majority, what early factors supported the evolution of electrical supply so that it could survive long enough to eventually attain competitiveness?

While we do not examine every factor relating to that question, our paper addresses it by asking the smaller scale question: in the first decades of electrification (1880s-1890s) what – or rather who – persuaded at least some wealthier householders to become consumers of electricity, and how did they do so when electricity supply had no obvious economic benefits over its older rivals? After all this a time when, unless one was lucky enough to be in a city region powered by a new (private or public) electric supply, the only accessible source of electrical energy was the expensive and less than reliable dynamo that was powered by localised water flow or in situ steam generators, backed up for emergencies by accumulator batteries. Such considerations are barely touched upon in Networks of Power, in which Thomas Hughes documents the systemic growth of local civic electrical networks, but does not seek examples of electrical installations that do not fit into his systems historiography. While Hughes’ analysis gives an indispensable starting point for comparative analysis of the growth of electrical supply in multiple countries, his grand teleological sweep into the mid-twentieth century obcures the economically necessary – yet harder to explain – persistence of electricity installations in less urban areas that lay outside of his systemic framework. Instead we look to a phenomenon only briefly touched upon by Hughes: the old money aristocrats, whose inherited wealth enabled them to be both sponsors and consumers of stand-alone installations of electric light while this particular illuminant was a luxury inaccessible and unaffordable to the majority.

In Domesticating Electricity, Gooday examined the significance of the stand-alone system installed at Hatfield House in the early 1880s by leading Conservative politician, Lord Salisbury. Far from fulfilling the stereotype of conservative, old-money aristocrat concerned primarily with husbanding resources, Salisbury was instead an active experimenter in electricity who sought to bring the new illuminant into Hatfield House even before the incandescent electric light of Swan and Edison was commercially available.3 Moreover, this country house installation, far removed from any local systems, was important as a much-reported locale for promoting the sociable value to fellow aristocrats of electric light via elite balls and dinner parties. As Gooday shows, however, owing to a workman’s death by accidental electrocution in 1881, Hatfield House also raised lingering worries about the deadly risks of electricity far more than other contemporaneous electrocutions of workmen in Britain.4 In two strongly contrasting ways, then, this particular country house electrical installation changed the cultural expectations of electricity far more than any of fleeting unsuccessful civic electrical systems discussed by Hughes for the early 1880s.5

What then does our work here add to the already substantial cultural history of electrification by Gooday and others? In previous cultural accounts of electrification, appeals have been made to ‘modernity’ as the alleged driving force,6 while some French sources appealed to la fée électricité as a fantasy figure of enchantment and enablement that symbolically enticed consumers to try its magical powers.7 But these ideological accounts simply beg the question; how do abstractions like modernity and fictional fairies actually do such persuasive work – where is their social agency? Our answer to this question instead concerns the cultural persuaders whose authority led this change of behaviour – the Victorian counterpart to the celebrity culture of 21st century actors and musicians who now lead campaigns for environmental change.8 Although perhaps counter-intuitive to some, the work of persuaders only seems so because their role is quietly erased from advertisers’ narratives to create the impression that consumption of a new product is natural and inevitable. While it might take a leap of imagination to appreciate this elusive empirical point, we can note that many of our 21st century common purchases started their career marketed as luxury goods, and only became mainstream mass-production items once the mass population was persuaded to adopt them as if they were necessities.9

This focus on celebrity endorsement for changing behaviours concerning energy consumption matters greatly since our paper considers a time when few civic consumers had ready access to electricity supply via a street mains. Indeed even for these consumers, it was not self-evident that the electrified home would or could furnish the optimal mode of domestic energy management. The appeal of gas-lit, coal-fired homes remained for many with conservative inclinations, unmoved by appeals to ‘modernise’ or oblige the electric fairy. The persistent growth in the supply and consumption of gas was of course a challenge for the proponents of electrification in many industrializing countries, including France. We thus draw our inspiration from accounts that focus on the persistence of pluralism in modes of energy management – rather than any uncritical acceptance of electricity. This is highlighted in Ruth Sandwell’s important recent edited collection Powering Up Canada where she shows that, for largely rural Canada, the rationales for choosing energy supply from wood or coal encompassed domestic consumers’ concerns for availability, sustainability, self-sufficiency and convenience.10 Upholding these priorities often mattered more to householders than obedience to the technocratic regimes of efficiency espoused as the key value of electricity supply. It is to explain this phenomenon that we seek to rethink the social agency operative in choices for or against electricity in UK domestic settings prior to the introduction of the National Grid.

It is in this vein that we return to Thomas Hughes’ seminal engineer-centred account to examine anew how far - for England at least – the development of electrical power was connected with the operations of social power, and gendered social power.11 We thus explore the importance of an alternative set of significant figures for electrification, examining how (far) the main drivers for this process included groups and actors previously given only incidental significance in standard accounts: wealthy aristocratic technophiles, female and male. At least some of these wealthy and influential figures were willing, able and did invest in autonomous stand-alone (non-grid) electrical installations. These were consequential in demonstrating the qualities of electric lighting, even while early urban systems could not prove commercial viability.

Back to topRevisiting Hughesian historiography

In examining the agency of aristocrats, we now consider Thomas Hughes’ treatment of them in his classic Networks of Power (1983), extending his treatment of the power politics of electricity.12 The absence in Hughes’ oeuvre of any reference to stand-alone generating plant in affluent Victorian countryside homes is a striking omission given Mark Girouard’s documenting of such houses twelve years earlier. In The Victorian Country House, Girouard notes that representatives of both kinds of wealthy Victorian upper classes, those from old money and new, invested in domestic electricity in the early 1880s, using water-power dynamos remote from any metropolis: the ‘new money’ ennobled industrialist Lord Armstrong at Cragside, Northumbria, and at the seat of ‘old money’ Lord Salisbury at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire.13 These early experimental country house installations lasted in place for decades, unlike the early electrical systems tried in civic locations which as even Hughes concedes could not muster a sufficient demand to survive beyond a few years: the city of London (as documented by Hughes), and the towns of Chesterfield and Godalming (as documented by Strange).14

Girouard held that country house electrification in this period was demographically most characteristic of the ‘technologically minded’ middle-class country house owners, citing such examples as Wright at Osmaston Hall (Derbyshire), Thorneycroft at Tettenhall (Staffordshire) and Walter at Bear Wood (Berkshire). Only being aware of two mansions belonging to ‘old families’ with early electrified homes (Hatfield and Eaton Hall, Cheshire), Girouard assumed that owners of inherited houses were under no great pressure to electrify them as long as ‘labour to carry coals, water and candles remained cheap.’15 Yet he did concede that further research might ‘alter the balance’ in his account of the relative significance of ‘new’ and ‘old’ money in early electrification.16 In that regard it is salient that both Girouard and Jill Franklin among others, opened up the idea of the English country house not only as a space of elite history, but as an important site to examine class-based social histories in the nineteenth century,17 leading later in the 1990s to some transformative gendered histories of these microcosms of the structures of everyday life.18 There has been very little analysis, however, that connects such historiographical re-examinations of the history of the country house and histories of electrification. We thus take up Girouard’s direction and begin to explore how far a claim can be made for the importance of (inherited rather than ennobled) aristocratic agency in the early electrification of Britain, in order to argue that old money house owners were considerably more at the forefront of non-systemic electrification project than either Girouard or Hughes had imagined.

To be fair, of course, Hughes’ account does note in passing the importance of aristocrats in two respects. The first concerns how they feature alongside scientists as a major audience for Edison’s first attempts at securing financial support and personal interest in his direct-current electric lighting system in the UK. Edison’s display at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1882 attracted considerable interest from Conservative politician Lord Alfred Churchill, the Duke of Westminster and the Duke of Edinburgh; although the Duke of Sutherland also admired Edison’s work, he had nevertheless already made a decision to install the Brush alternate current system (apparently following Lord Salisbury’s example) at his Stafford House residence in London. Hughes is explicitly clear why this aristocratic audience mattered: Edison’s UK agent Edward H. Johnson sought to demonstrate Edison’s technology not only in centralized city installations but also in small isolated plants in ‘great homes and country estates’.19

Yet Hughes does not examine the latter issue any further – perhaps because the Edison company secured no contracts with the nobility. Instead Hughes focuses on the troubled career of the short-lived Edison supply station installed at Holborn Viaduct, which from 1882 supplied the City of London, ensuring that London’s major financial institutions saw the displays of Edison electric lighting provided from Holborn Circus to St Martin’s le Grand (location of the Post Office headquarters), as well as to private householders. Nevertheless, as Hughes reports, in order to compete with gas utilities on cost to the consumer, the Edison Company had to operate Holborn with loss-making price tariffs for electricity supply. After four years of such heavy financial subsidy without winning over long-term customers, the Edison company abandoned this project and the area reverted to gas lighting. Although he follows Edison in attributing this commercial failure to the adverse effects of new electrical lighting legislation in 1882, Hughes’ evidence is clearly that Holborn customers preferred gas supply even when Edison supplied electricity at the same price per unit.20 As we see below, however, Hughes’ second comments on aristocratic sponsorship by Lord Crawford and Lord Wantage of electric lighting installation at the Grosvenor (Art) Gallery in London’s West End, informs our argument about the cultural standing of electricity as a luxury for the elite. That, we maintain, can explain its early take-up when purely commercial considerations did not favour it.21

Another key point of reference on the standing of early electric lighting as luxury can be found in Adrian Forty’s classic discussion of ‘objects of desire’. Forty emphasises that technical innovations are not inevitably incorporated (or ‘diffused’) into everyday life: there must be a specific reason for their take-up. For the case of early electrical consumption, he notes that even by the onset of the First World War, the domestic consumption of electricity in the UK was still negligible by comparison to other industrial sectors, and had barely increased since 1895. He diagnosed this as arising from ‘the high price of electricity and the considerable cost of wiring a house’ which ‘restricted the clientele to the well-to-do’ along with fear of electricity, and its greater cost yet lower accessibility than gas. Forty notes that this required encouragment from marketing efforts of the supply industry.22 In our exploration of some electrical industry advertising below, we show how this marketing was often taken in partnership with the aristocratic consumers. It was their ability to both afford electricity and also display its use in a spectacular way to both their peers and the publics who visited their country houses that was a crucial in persuading others to adopt this new form of energy supply in their homes.23

In this regard we follow David Cannadine in arguing that in the case of England the key cultural authorities in leading lifestyle choices remained the aristocratic upper classes, at least until the First World War.24 That being said, we consider in somewhat more detail than Cannadine the gendered nature of aristocratic agency. The gendered nature of transformative social agency in technology is a theme only recently addressed in the literature on early electrification which was previously attributed largely to men.25 Specifically we build upon Gooday’s early research to explore some examples of elite women who were actively engaged in trialling and promoting electricity in England and analyse why their example was so important for middle class women, who were increasingly securing authority in our period to make major domestic decisions about such matters as lighting technologies. At a time when women were consistently made aware of the risks of ‘getting it wrong’ in terms of taste and behaviours, in a country that has always been dominated by questions of class prerogative, how far did the elites influence the turn to new forms of power in the home?26

Overall our evidence is beginning to show that by agreeing to light their houses by electricity as very early consumers, British aristocratic elites, female and male, both publicised the new illuminant to the bourgeousie – who were sought to emulate them – and supplied opportunities for professional entrepreneurs and electricians to hone their skills in the initially very challenging business of electrical installations. They thereby supported the new electrical industry at a time when it could not offer the economies much later brought by modern ‘grid’ a.c. networks. Before then, we should highlight a point mentioned above that electricity seemed for many in the England to be both more expensive and untrustworthy than other energy media - a suspicion only enhanced by the lack of cost comparisons in literature directed at consumers.27 According to one estimate, the average cost of a domestic electrical installation in 1890s England was £50 – roughly equivalent to the entire annual wage of an average worker.28

We can thus see why the late nineteenth electrical industry had to work hard to counter this impression of electricity as an (unnecessarily) great expense. As Brian Bowers has noted, ‘Those who wanted to sell electric lighting needed to be very vigorous and persuasive in promoting their wares’, and hence their advertising focussed on such themes as spectacle, attractiveness and patriotism, rather than cost.29 In her handbook Decorative Electricity of 1891, a work dedicated to persuading middle-class women (and men) that electric lighting could be adopted in the home in an artistic and elegant fashion, Alice ‘Mrs J.E.H.’ Gordon - spouse of consulting electrical engineer James Gordon - admitted that the average hourly cost of operating an electric lamp was one farthing, twenty per cent greater than for its gas counterpart.30 Nevertheless, she claimed that this extra cost was compensated by the economy which could be effected by immediately switching electrical lights on and then off as one entered and then left a room - a practice that was unfeasible for gas lighting in the period.

Notwithstanding Mrs Gordon’s claims for potential parity with the costs of domestic gas consumption, the tone of Decorative Electricity was indeed distinctly to emphasise its luxurious potential for a wealthy social elite. Alice’s advice was that consumers should budget not only for ‘practical’ everyday lighting, but also for luxuriantly aesthetic ‘decorative’ lighting to be used for special occasions: her own house was lit with 42 lamps for the former purpose and no fewer than 87 for the latter ‘occasional’ use!31 Unsurprisingly, such was the indifference or even distrust of less affluent female householders towards electric lighting, that the Electrical Association for Women was founded in 1924 - as a side project of the United Kingdom’s Women’s Engineering Society- in order to help create a domestic demand for electricity. This task was quite successfully accomplished by strategically deploying the authority of women - notably that of first EAW President, Lady Nancy Astor, MP, in building female consumers’ trust in the new illuminant.32

We explore below the critical patronage of the aristocracy in early British electrification seen in the autobiographies of British electrical manufacturer and entrepreneur, R.E.B. Crompton and Lady Randolph Churchill. This case is important to highlight since it reveals how the entrepreneurs selling early electrical systems in England needed social elites to ‘advertise’ the new illuminant as glamorous luxuries. The alleged modernity or efficiency of electric lighting was irrelevant or commercially useless in this context. In particular, upper-class women were vital to the social normalisation of electricity as suitable for elite consumption – although they did not necessarily see their role in the same terms as the entrepreneurs that they dealt with. We thus address next how domestic electricity was constructed initially as a luxurious enterprise, relating this to how aristocratic patronage became a valuable element in electrical engineers’ practices of persuasion in the earliest phase of electrification.

Back to topThe electric culture of the celebrity aristocrat client and middle-class emulation

As Gooday has shown, the early public identity of electricity supply in England in the 1880s was of a garish, risky, expensive luxury33 with the fast-growing gas industry providing a more affordable - and more readily understood - energy alternative.34 So to return to the question that we raised in the introduction: how can we explain the growth of demand for pre-grid electricity? We must look beyond purely technocratic parameters. Among a range of cultural factors which could be explored, we seek specifically to recover the critical role of aristocratic patrons in the first stage of the transition to widespread adoption of electric energy – not merely as customers for, but as active allies of, the electrical industry.

There is a broader pattern to this that relates to longer-term concerns about energy management. As noted above, numerous scholars in this field have observed the importance of the environmentalist cultural advocacy of 21st century celebrities who were not practictioners of Science, Technology, Engineering or Medicine [STEM] in music, television, sport and film which has been vital to changing public opinion about climate change.35 Correlatively we explore how far and in what ways the celebrity pantheon of fin-de-siècle aristocrats supplied cultural leadership for changing energy consumption to the electrical mode among the wider public. When the immediate benefits of changed behaviour were unattainable or invisible to the wider populace, we show that leadership in the life-style change for electricity leaned heavily on the authority of aristocratic agency and personality. Since the advent of electricity supply alone cannot explain its take-up, we see here the prospect of a new kind of explanation for how demand for electricity was first nurtured, avoiding assumptions about the inevitability of the phenomenon we aim to elucidate.

In documenting eminent politicians’ powerful support for electrical systems-building in London in the later 1880s, Hughes notes the catalytic role of Lord Wantage as a wealthy upper-class investor in early electrical supply technology. Specifically he shows the electrification of the Grosvenor (Art) Gallery in London was premised upon collaboration with Sir Coutts Lindsay’s building construction and financial support from his wife as a member of the Rothschild family.36 Yet Hughes’ supplier-focussed study does not then go on to discuss systematically the class profile of the first consumers for this new technology: for us, it this class-profile of consumers that is crucial to understand.

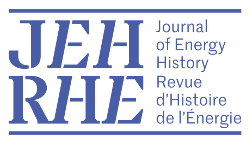

Hitherto overlooked evidence of the significance of upper-class consumers is clearly present in early advertising by electrical installers. Instead of advertising electricity as an efficient system-based technological utility (as one might have expected from reading Thomas Hughes’ interpretation), the countervailing associations of aristocratic patronage are most evident in the marketing of this very expensive new technology. Such publicity listing the nobility as their principal customers can be found in the front leaf and rear-leaf advertising introduced to the second (1892) edition of Mrs J.E.H. Gordon’s Decorative Electricity (first edition 1891).37 See for example the advertising by Woodhouse, Rawson & Co at the front of this work, and Verity & Sons at the rear. The pre-eminence of powerful aristocratic male customers listed in these advertisements indicates that their households had been significant among the first domestic locations targeted for electrical installations, although the listing is a matter of social hierarchy rather than chronological sequence. Clearly while institutions in central London are also highlighted as customers for electric lighting in these 1892 advertisements, the preponderance of space is given to aristocratic consumers, and they are listed first (at least in the case of Verity and Sons):

For Woodhouse and Rawson we can see only the most elite are mentioned, the Marquises of Salisbury and Ripon on the right hand side, with the aristocratic Hon.Thomas Brassey (later Second Earl Brassey) to follow; listed last – with some evidently prejudicial ethnocentrism – the Maharajah of Mysore, an autonomous city-kingdom in Southwestern India lying outside the British empire. For Verity and Sons, if we look at the descending order of the aristocrats advertised, we see that they follow the conventional order of ranking: the Duke of Fife followed by the Earls Rosebery and Cadogan, all the way down to institutions, MPs, and Esquires. Later we will explore the significance of the 6th ranked aristocrat, Lord Randolph Churchill (with installations by another contractor, Crompton and Winfields) noting that in fact Lady Churchill was the chief figure of interest. Another point to note is that both companies attached considerable value to highlighting the clientele of prestigious (London) institutions, each claiming to have had the Stock Exchange as a client, but otherwise they were complementary in their track records of services. The very fact that these two companies advertised their services citing male aristocratic customers in a book written for (mostly) female middle-class consumers that highlights the gendered complexities of the issue. The aristocratic couples were implicitly fashionable leaders to follow.

Following this example, we can also turn to the text, frontispiece and end-piece advertising of later editions of Mrs Beeton to see how they echo these aristocratic preoccupations. The 1907 edition of her Book of Household Management declared that that ‘cooking by electricity is now quite practicable, though for the present decidedly expensive’, such cost meaning it was only in reach of those with the most money, i.e. the elites. Certainly the author of the 1907 edition of Beeton knew how to ‘sell’ electricity via association, citing the fact that ‘the King’s yacht (constructed for her late Majesty, Queen Victoria) is fitted up with a complete electric kitchen outfit, including soup and coffee boilers, hot-plates, ovens, grills and hot closets’.38 Beeton’s success drove the development of the mass market for cookery books, that we would see used to push the cause of gas or electricity in the late nineteenth century, for example Jenny Sugg’s The Art of Cooking by Gas (1890), or Amy Cross and Alys Waterman’s How to Cook by Electricity (c.1910).

Each of these books including later editions of Mrs Beeton, contained advertising material, aiming to persuade women to either adopt electricity or gas into their home, and we also can find examples of how the country house was used to evidence how the very best household’s employed the newest forms of energy. For example, the 1910 Smoke Abatement Exhibition, held in Glasgow, advised on ‘Lighting and Heating, Cooking and Power’ by electricity using recreations of country house interiors complete with Chippendale-esque furniture supplied by Messrs A Gardiner and Sons of 36 Jamaica Street, under the heading ‘Electricity means Cleanliness’. The exhibition catalogue included adverts for ‘Country House Electric Lighting’ by Mavor and Coulson Ltd. of 47 Broad Street, Glasgow, with a photo of Overtoun House in Dumbartonshire used as an example of ‘one of the many houses which we have equipped for Lighting, Heating, Ventilating, Pumping and Hoisting by Electricity’.39

Aristocratic and Middle-class Role Models of Women Shaping the Home

As we can see from the advertisements from Verity and Woodhouse & Rawson above, the Duchesses and Dukes, Ladies and Lords – of old and ‘new’ money – adopted exemplary celebrity roles in setting a trend for adopting domestic electricity as a fashionable and elegant mode of consumption.40 Their role, we suggest, thereby nurtured symbiotically the industry of electrical consultants and contractors, and the newly emerged profession of the professional female interior decorator. This is the only way that can we explain why the advertising of such contractors from the 1890s recurrently highlighted aristocrats as their principal clientele. Who else but these wealthy elite would have had the leisure and finance to invest in such a risky and controversial new technology as domestic electricity? And how else would electrical engineers have found the finance and opportunities for the early projects of electrification without noble patronage and finance – a topic not acknowledged in conventional engineering historiography.41

While this history of women as crucial for the growth in the consumption of electricity in the home has been lately focussed on the new role of the middle-class woman, we focus here on their aristocratic counterparts who had continued to offer the newly monied a long-lived example of how women could and should operate in their homes and the external world as members of a privileged social and political elite.42 Electrification in England began at the end of a century which had seen a significant shift in the class systems with the development and enrichment of a newly monied ‘middle’ class. Economic transformation arising from industrial growth led to changing expectations of the roles of men and women in all social classes. With an increasing separation of home and work on gendered lines, society enabled and expected middle-class women to manage their homes in new and for some, more empowered ways.43

While we argue here that middle class women were being empowered by this new requirement to manage the home, including energy supply and use, they were concurrently made deeply aware via a growing range of advice and etiquette guides that to ‘get this wrong’ risked social exclusion for them and their families.44 Empowerment came at a cost, with a set of very complex social challenges attached, hence the need to look to those who had always been presented in British society as representing ‘right and proper’ practices - the aristocracy. As Thorstein Veblen argued in The Theory of the Leisure Classes (1899) the emulation of aristocratic patterns of consumption in the home offered one way for middle class women to meet the increased pressure accorded by their new roles as house wives and managers.45 Veblen was examining American society with a class structure founded in wealth rather than birth: in the U.S. case the cultural leaders in electrification included the ultra-rich business couples Mrs & Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt and Mr & Mrs J.P. Morgan.46 For the case England, where the constant dance of class and reputation was determined by being seen to do, know and consume the ‘right things’, Veblen’s concept of emulation is useful for explaining why middle-class English women would look to the aristocracy for examples of ‘good’ consumer decisions.

The development of the idea of the home as a legitimate sphere for women to take charge of, encouraged by the books and advice guides written by Victorian middle-class commentators, has been carefully documented by historians both in England and in the USA.47 In John Ruskin’s words, the mythical ideal of the ‘Angel in the House’ saw middle-class women as guardians of the home as ‘a sacred place, a vestal temple’ tasked with the role of managing all aspects of domestic life, including lighting and heating.48 The ideological and practical expectations for aristocratic women were very different indeed from those of their middle-class counterparts. Kim Reynolds notes importantly that aristocratic homes and families were constructed ‘in relation to an entirely different ideological model’, and indeed a very different financial model. Aristocratic women were neither expected to confine their entire life’s activities to the care of their husbands and children or their homes. They were ‘not defined in strict contrast to the men of their own class’ since neither aristocratic men or women went out of the home to engage in paid labour.49 While their roles were assuredly gendered, it was not within the context of ‘oppositional and mutually exclusive categories’ widely thought to define the lives of late Victorian middle-class women’.50

As the mistress of an entire estate or a collection of town and country houses, an aristocratic woman was conventionally expected to fulfil specific social, spiritual and economic obligations. The aristocratic household in the nineteenth century continued the tradition of the country houses and London palaces of previous generations, so carefully mapped by Mark Girouard.51 Far from being ‘places of retreat’, Reynolds emphasizes that these were the ‘public arena’ in which the aristocracy ‘reinforced and reinvented its power’.52 Most important of all, these were public spaces of spectacle which were presided over by aristocratic women. Thus in contrast to conventional middle-class homes, such households were ‘sophisticated tools’, used to uphold the status of the family. As Reynolds emphasizes, aristocratic households were ‘political structures’, their wealth-giving estates lending them an extensive economic role which had ‘no counterpoint in the bourgeois home’.53

How much aristocratic women were responsible for the maintenance of the household varied according to the size of the home and historic traditions. In larger households, for example, Reynolds’ case studies demonstrate that daily superintendence was placed in the hands of an upper servant or agent (usually male); in such cases she likens the role of the aristocratic women to that of a company director.54 Therefore, while we can see that aristocratic women had a different role to play in household management and patronage to their middle-class counter-parts, they continued to take on powerful leadership roles in the nineteenth century and acted as important role-models, persuaders and consumers, for our purposes, in the successful incorporation of electricity into the home.

This incorporation of electricity into the aristocratic home came in an increasingly anxious time for this privileged elite world when change was afoot. From the 1880s to World War 1, the authority and status of the British aristocracy were most effectively challenged by the economic dominance of rising middle classes at a time when the agricultural depression was sharply diminishing the income of the land-holding aristocracy. Thus finding (new) ways for the aristocracy to demonstrate its continued power, in town and country, remained and perhaps increased in importance. Their homes were vital spaces in which aristocratic women and men could express their dominance, taste and wealth, especially as they began to need to compete with the new builds of the nouveau riches.55

As Reynolds puts it, the ‘exercise of hospitality’ continued to demonstrate aristocratic social standing, so too did aristocrats’ capacity to advance clients by offering them employment or the means of subsistence. That scope for offering patronage remained ‘an index of the power of a noble family’.56 At the same time as fulfilling the ancient prerogative of noblesse oblige, the behaviour of the glamorous upper classes was also scrutinised by many among the middle classes as a model for their socially upward aspirations, including the consumption of lighting. Within these twin contexts we later explore the relationship of aristocrats with the entrepreneurs of electrical engineering who sought to tap into this world of privileged patronage to promote their expensive new technologies.

Before that, let us note how women in the rising middle-classes were by no means exclusively reliant on upper-class models for the development of their domestic havens, and yet the influence was ubiquitous. Among the household manuals that became the key source of guidance for the aspirational middle-class woman in our period, the most famous and long-lived in England was Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management.57 While the aristocratic lady was certainly not the intended reader, and although it was specifically addressed to ‘The Mistress’ of the house, the aristocratic mistress could be seen very much as an inspiration rather than a consumer. Mrs Beeton, in her guidance, focuses on taste and society, and as Margaret Beetham says, in the text ‘the way food was prepared, presented and consumed’ by the women of the household became a marker of ‘important social differences’.58

Mrs Beeton makes a clear distinction between raw and cooked food ‘as the marker of the transformation of nature into culture’, and the way that food is transformed, the energy source utilised for this in the kitchen, became an important part of her instructions to middle-class women either cooking themselves or managing servants and housekeepers.59 Obviously in 1860 only a coal or wood fired stove for cooking could be imagined but as we have seen, later editions dealt with the possibilities of cooking using electric. But it was not just Mrs Beeton and similar household guides that inspired change among middle class women’s behaviour: writers on the decorative aesthetics of lighting also played a key role in the campaigns lobbying for changing modes of energy consumption.

Harrison Moore’s recent research on the first British women decorators and women authors on interior design has highlighted the importance of Mrs. Mary Eliza Haweis’ The Art of Decoration (1881). Decorating was one of the first professions opened up to middle-class women in the 1870s, as it was quickly realised that as women started to have shopping opportunities greatly enhanced by the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, they were receptive to and often reliant on advice on how to decorate their homes.60 Combined with the increasing pressure on middle-class women, as the ‘angels in the house’, to provide a moral, heavenly space for their families, was the need to demonstrate their knowledge and taste in interior design, and, consequently make lighting decisions in the home.

Haweis’ text includes the first positive reference to lighting and heating the home by electricity written by a female author we have found to date. In recommending electricity as the best way ‘to light adequately a large room without heating it,’ Haweis makes specific reference to the electric lighting introduced by Lord Salisbury at Hatfield House, examined as a key site of electrical innovation and experimentation by Gooday’s Domesticating Electricity.61 And as we saw previously, while Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management in 1907 used the example of a luxurious boat, a Royal yacht was at the apex of aristocratic examples of the domestic employment of electricity. Each of these types of text were crucial in framing these spaces and their aristocratic owners as exemplifiers of the most progressive sort of energy use, and we can see how this rhetoric helped to sell electricity even when it was by far the more expensive way to heat and light the home.

Back to topWomen of Power in Electrification

In looking at how Verity and Woodhouse & Rawson cited aristocratic clients in their advertising, one might infer (wrongly) on a Hughesian reading that these upper-class consumers were entirely passive recipients of the new systems technocracy. After all British aristocrats, male and female, have long (falsely) been assumed to have made no significant innovations since enacting canals and agricultural improvements in the Georgian era.62 Yet, building on Cannadine, we challenge this misguided caricature of fading aristocratic agency. Whereas Trentmann’s analysis in Empire of Things (2016) treats aristocrats as leading consumers of new luxury goods only up to the early modern period, and only in non-European settings, we show that their engagement with innovative technologies was still crucial in Victorian and early Edwardian England.63 Our new culturally inclusive approach to electrification is guided by Trentmann’s more recent (2018) inter-disciplinary writings on ‘Getting to grips with energy’ that is informed by insights from cultural anthropology:64 ‘how people use energy relates to how they value it and thus what it enables them to accomplish’.65 For early electricity, the accomplishment that we trace is the performance of luxury consumption. In that sense we follow Trentmann’s injunction for future research on energy to tell a richer story ‘with the people put back in it’. This involves focusing on both aristocrats and engineers, with aristocrats featuring among financiers, consumers and engineers. Most importantly it involves looking at how female aristocrats carried a significant persuasive power in their innovative use of electricity. Although we see that the language of agents and agency adopted was not commonly agreed between the parties concerned, we can understand perhaps how it was the promotional work of Jenny, Lady Churchill rather than Lord Randolph Churchill who accrued the epithet of ‘advertising agent’ from the electrical contractor-entrepreneur Crompton.

The case in point is the electrification c.1884-85, of Lord and Lady Churchills’ town house at 2 Connaught Place, in the elegant Marble Arch area of West London, over-looking the north side of Hyde Park. Looking back to their occupancy of this house for the decade from c.1883, with sons Winston and John, in her 1908 autobiography, Lady Churchill presents this as a matter of her own pioneering agency as the ‘first private house in London to have electric lights’. Nevertheless, she also notes in passing late in her narrative that this was ‘gift of an installation’ and served as ‘an advertisement’ for the company which had ‘offered to put into our house free of cost’.66 She makes no explicit mention of the gifting manufacturer and contractor, Crompton. Instead she looked back on this heyday as when the Churchills were so fashionable that it was only natural that any entrepreneur wishing to promote a novel commercial enterprise would come to their family, and offer this novelty gratis in order to show it to the rest of their elite social circles. And their innovation was certainly noticed by neighbours. As Lady Churchill writes of an era well before any local grid networks were available, and at a time when the first electricity supply legislation was passing through the House of Commons, their only supply of electricity was from a (presumably coal-fired) basement electricity generator:

We had a small dynamo placed in a cellar underneath the streets, and the noise of it greatly excited all the horses as they approached our door. The light was such an innovation that much curiosity and interest were evinced to see it, and people used to ask for permission to come to the house.67

The recurrent fallibility of this dynamo, however, necessitated fetching lamps and candles from the same basement to keep dinner their parties illuminated (see discussion in Domesticating Electricity). More than that, however, there were legal and financial complications arising from having this as a gift:

The electric light did not prove to us an unmitigated blessing, inasmuch as Randolph having spoken enthusiastically in the House of Commons in favour of an Electric Lighting Bill,68 felt he could no longer accept the gift of the installation which by way of an advertisement a company had offered to put into our house free of cost. Unfortunately, there being no contract, we were charged double or treble the real price.69

A somewhat different view of this installation is apparent in the writings of Rookes Evelyn Bell Crompton, a mechanical engineer and military veteran of the Indian Empire. His mechanical engineering company based in Chelmsford, Essex, quickly adapted to electrical engineering when the commercial opportunities for Swan and Edison lighting emerged in c.1882. Using his imperial connections to gain access to the gentry, he sought out upper class patrons to promote the expensive and rather hazardous innovative dynamos that his company manufactures. While it was male aristocrats who had the financial resources to pay for such indulgences it was evidently the social caché of the female aristocrats that was most important in such situations. Indeed writing his autobiography seven years after Lady Churchill’s death in 1928, he cast her role as that of ‘advertising agent’ – a representation which she herself would not have accepted – and highlighted details of her boudoir arrangements that would doubtless have been less acceptable to publish 40 years earlier:

Both Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill took great interest in our electrical work, and Lady Randolph became most useful as an advertising agent. She delighted in showing off to her friends of the fashionable world our various electrical appliances, among them a pear-shaped switch, christened ‘the Randolph’, which enabled her ladyship to light up or switch off without leaving her bed… 70

Such was the effectiveness of this advertising by Lady Churchill that Crompton’s soon gained other affluent customers:

We also put in installations at [Attorney-General] Sir Richard Webster’s in Hornton Street, Kensington; at [chemist and journal editor] Sir William Crookes’ house and laboratory in Ladbroke Square; at [Sir William Schwenk] Gilbert’s, the well-known dramatists in Harrington Gardens; and in many other private houses and shops. Siemens and other rival manufacturers soon began to copy us, but I claim that we, ‘Crompton’s,’ introduced the arrangement, and that these private installations were the chief means of popularising the electric light, and caused the demand for its use which now began to arise. 71

Crompton’s citation of Lady Churchill as his ‘advertising agent’ highlights the persuasive agency of women, as epitomised in Mrs Gordon’s well-selling Decorative Electricity in 1891: although we have no circulation figures for that first edition, the cheaper second edition was produced in 1892, just six months later. By this time, Mrs Gordon could declare in her preface that the economics of electrical lighting had been greatly improved, so that is was by then prudent for consumers who could afford only five electric lamps not to install them in their home.72

Nevertheless, our research wishes to look beyond Crompton’s account since Lady Churchill’s Reminiscences (1908) gives a different view of her role in domestic electrification, emphasizing her autonomy. The significance of aristocratic women in the histories of electricity is further evidenced in later decades where we see aristocratic women still leading in related technological enterprises: the Women’s Engineering Society was founded by Lady Katharine Parsons in 191973 and the Electrical Association for Women adopted Lady Nancy Astor as its first President in 1924.74 Drawing on Reynolds’ Aristocratic Women and Political Society (1998) we want to situate this electrical activity in the period when, as the broader socio-economic power of the aristocracy was coming under strain, upper-class women’s role as patrons in domestic, social and political matters was ever more visible and significant. The role of the wife, both of the engineer and consumer of electricity is a key but often missing part of a gendered history of electricity.

Having seen the importance of the gendered aristocratic role in electrification of the town house, what then of the other major residence of the upper classes: the country house?

Back to topThe country house as a strategic site of patronage and electrical display

As Girouard influentially pointed out, the country house is an important site to examine class-based social histories, and therefore it is vital that we turn to this as a strategic site of aristocratic electrical display.75 Investigation of how traditional upper-class homes served as sites of technological innovation was given recent impetus by Barnwell and Palmer’s (2012) Country House Technology, and Palmer and West’s (2016) Technology in the Country House.76 These works explore how the selective introduction of new technologies changed country house life in the nineteenth century, while noting that not all homeowners chose to invest in new technological systems. This research, when read alongside David Cannadine’s influential narrative of aristocratic adaptation and survival during their alleged decline as a class following the 1880s agricultural depression,77 requires us to move beyond Girouard’s assumption that old money aristocrats were largely too conservative for electricity.78 Especially original is his focus on aristocratic support for new industries of power and mobility, including automobiles and aeroplanes, as a bulwark against declining income and influence. Our class-sensitive narrative follows Cannadine and Edgerton79 in challenging the controversial yet still popular and republished declinist allegations of aristocratic opposition to technoscientific innovation.80 Extending that critique to the history of electrification, we build upon exploration in Gooday of two electrical engineers who inherited aristocratic titles: James Swinburne as Baronet and the militarily credentialed Kenelm Edgcumbe.81 We thereby extend Cannadine’s key point that younger male members of aristocratic families often took up engineering, thus working at the intersection of the networks of nobility and technology.

So what were the broader driving forces that brought modern engineering into England’s older aristocratic households? Cannadine has examined how aristocratic males helped to develop railways, automobiles and aeroplanes, and we extend his study to the emerging electrical industries of lighting and power, highlighting collaborations forged between entrepreneurs and professional engineers. While important studies, neither Hughes nor Cannadine gives a systematic and symmetrical account of how the gentry collaborated with technical experts in accomplishing early electrification. So the challenge remains of examining how they interacted, and how far their respective contributions were essential to the enterprise. We can find parallels in historical accounts of how scientists and aristocrats in comparably fruitful interaction in research activities.82

It is key in our work to distinguish between old and new forms of money involved in supporting these extremely expensive ventures. This is especially significant given the previous analyses that have cast English aristocrats as if they were reactionary electrophobes, who rejected the adoption of this new-fangled technology as being only modern play-things of the nouveau-riche. We have already examined the importance of Hatfield as an aristocratic house that evidenced both the spectacle and the dangers of electricity.83 Fear of the new might also explain why, at Chatsworth, Drake and Gorham, one of the leading companies of electrical engineers of the day, worked hard to balance the newest of technologies with the historic decoration in a house that dated back to 1553. In articles announcing the installation of electricity in 1893 at the country house in Derbyshire, the firm worked hard to reassure readers that the new electric fittings perfectly harmonised with the pre-existing decoration; ‘with such consummate skill has the electric light been introduced, where hitherto candles and lamps had reigned…Indeed, whenever possible all the existing standards, brackets and chandeliers and so forth have been utilised, and where there were none the incandescent lamp has been introduced to look as if it had been there from the beginning’.84

While they may have emphasised the way that they fitted electricity into historic interiors, it was perfectly clear from this and other reviews of the electrification of Chatsworth written in the 1890s, that the ambition was to also celebrate the innovative and forward-looking nature of the family in their home. The author of ‘The Electric Light at Chatsworth’ concludes that, all ‘who see the house with its new illumination will see a thousand excellences that they never suspected to exist’. As Marina Coslovi has noted, when the ‘era of electricity’ arrived, Chatsworth was among the very first of country houses to install electric lighting; she also reminds us, that as a very significant aristocratic family, in a house that represented generations of inherited land-ownership and power, they did this at a time when some looked down on electrification as ‘a “nouveau-riche” indulgence’.85 As Jocelyn Anderson observes, Chatsworth was one of the grand country houses which had powerful public identities and had become ever more accessible to tourists since the Eighteenth century, and by the time of its electrification, visiting such houses had indeed became a very important part of the cultural life of England. While we do not have the numbers of visitors who visited specifically to see the electrical innovations in the house, we can surmise that electrifying a country house ensured a significant audience for this new technology.86

Baedecker’s eponymous guide said in 1890 that Chatsworth was ‘redolent of modern’87 and the electrification of the house was widely reported on. Coslovi confirms that ‘electricity was introduced into country house with much more enthusiasm than gas had been’, as it had clear practical advantages, especially in terms of the impact of gas fumes and dirt on interiors, textiles and art. The electric lighting of Chatsworth was followed with interest by the local press, with the Nottinghamshire Guardian and the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent both featuring articles in December 1893 as the project was revealed to the public. The writer from the Nottinghamshire Guardian concluded that all ‘who see the house with its new illumination will see a thousand excellences they never suspected to exist’.88 The archives at Chatsworth show that the cost for consumption of oil and candles dropped to zero in 1894, which Ian Watt uses to suggest that electrification had won the day there.89

It is useful to consider the different roles of the aristocratic country and town house in the introduction of electricity. Both had key roles to play. From a marketing standpoint, town houses were highly visible sites of technical demonstration, since they were located in populous cities. In contrast, country houses could be seen as being less visible, since they were geographically isolated, but as we have demonstrated, the importance of these houses as public spaces of display was equally valid in the history of electrification because of the long histories of tourism and country house visiting. Within the peer groups of the wealthy, aristocratic or nouveau, the culture of balls and dinners, so vital in patterns of social class and respectability, ensured that those invited would travel long distances to be entertained in the shining homes of the elites. This was precisely why Lord Salisbury chose a ball as the perfect way of showing off electrification at Hatfield, while advancing and confirming his political credentials (see above).

As an example of the influential significance of electric lighting in country houses, at Chatsworth there was an interesting relationship between the early electrification of Chesterfield, the town closest geographically to the House. Chesterfield was very much a part of the Devonshire family estates and holdings, then and now. This town experimented with and subsequently adopted electric street lighting in 1881 using the engineering firm of Hammond and Co., 12 years before Chatsworth was electrified internally by Drake and Gorham in 1893. The town reverted to gas again in 1884.90 Street lighting, however, is a very different type of electrification to domestic lighting, and one might imagine involves less of a concern over potential risk, given it is outdoors and not in the home. The Dukes of Devonshire, including the 8th (1833-1908) and 9th (1868-1938) Dukes, were actively involved in Chesterfield, and the town’s coal mines were part of the family holdings.91 Both Dukes were MPs for West Derbyshire, the 9th Duke became Mayor of Chesterfield in 1911 and the family took an active interest in the management and governance of the town. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the experiments in electric street lighting and the role of the town as a pioneer in the history of electrification would have been of great interest to them and, despite ultimately proving unsustainable in the 1880s, may have influenced the decision to electrify Chatsworth. Whereas the Chesterfield experiment was short-lived it was significant and as Patrick Strange concludes ‘served to bridge that important gap between experiment and commercial reality’ in street lighting, that Chatsworth helped bridge in terms of lighting the home.92

Looking beyond the immediate topic of electrification, such country house case studies offer a new perspective on technological change in fin-de-siecle England that recovers the agency of upper-class innovation at a time when the House of Lords was still largely the national seat of power. Challenging myths lingering since Wiener’s allegations of British high culture’s hostility to innovation, we have revealed a broader vista of co-operative networks of aristocratic and entrepreneurial agency which can be expanded in future research.

Back to topConclusion: mapping the networks of symbiosis

Our new research project is at an early stage, but we have begun to map the co-evolving worlds of aristocratic influence and engineering agency that are a hitherto-unexplored characteristic, we argue, in facitiliating the early stages of electrification in England. Of course, we do not claim that it was solely aristocratic patronage which faciliated this change: the participation of old-money aristocracy is only one factor in the broadening system of new electrification. But as part of a longer project we have identified which elements of social power have been missing from the classic narrative of Hughes.

While there is much left still to do, we have specifically brought together for the first time: i) the aristocratic networks of developing electricity consumption at client country houses ii) and the four major early entrepreneurial agents of electrification: Cromptons, Drake & Gorham, Verity & Sons, and Woodhouse & Rawson for whom the aristocrats were clients.93 As we have seen Cromptons relied on Lady Churchill to ‘advertise’ their wares, in preference to the more declassé practice of advertising in popular literature. Indeed in mapping out the growth of early electrical lighting in country houses we have begun to clarify how far pre-existing social interactions between country houses led to a successful ‘word-of-mouth’ model of securing new clients without paper advertising. This appears to have been the means by which Drake and Gorham, for example, secured social patronage. As we showed above, the two other entrepreneurs that we study clearly did rely on the newer methods of advertising to capitalise upon their upper class connections in the second edition of Alice (Mrs J.E.H.) Gordon, Decorative Electricity (1891).

Future research in our project will looking at how such companies published company reports of their aristocratic clients e.g. in the Times, Electrician etc. to reassure shareholders that their support of new electrical businesses like theirs was a good investment. Rather than being autonomous and self-sufficient, as assumed by Thomas Hughes classic account, we aim to show how these entrepreneurs needed the custom of prestigious aristocratic families to build their careers. In turn, this symbiotic mapping will show how those aristocrats benefited from showing themselves able to demonstrate to their guests the most exciting new technologies. In an age when aristocratic power was waning (through the weakening agricultural industry of the time), we will highlight further how owners of the great houses needed the symbolism of success and innovation that electricity in high class houses could bring.

Looking to the agency of women as a key part of the future research avenues at the crossroad of Gender studies and Energy history, we will look for more stories like those of Lady Randolph Churchill ‘showing off to her friends of the fashionable world’ the new electrical appliances given to them for demonstration purposes by ambitious entrepreneurs such as Crompton. Future research will look, for example, at how Queen Victoria’s interest in the spectacle of electric light at Waddesdon was piqued when one was turned on and off when she visited this house in 1890.94 Focusing on the role of such powerful women as Lady Churchill and Queen Victoria will enable us to rethink the balance of the key factors of class, gender and entrepreneurship in seeking to explain afresh how early electrification occurred in England. More than that, the international and imperial connections of such eminent figures will be a starting point to considering who led the take up of electricity in other countries other than the United Kingdom.

- 1. Leslie Hannah, Electricity Before Nationalisation: A Study of the Development of the Electrical Supply Industry in Britain to 1948 (London & Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1979); William Hausman, Peter Hertner, & Mari Wilkins, Global Electrification: Multinational Enterprise and International Finance in the History of Light and Power, 1878–2007 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

- 2. While the subsequent ‘National grid’ covered the entire United Kingdom, constituent nations had their own stories in preceding phases of electrification. Here we focus on the case of England; for Scotland and Wales, with comparative discussion on Canada and Sweden, see Paul Brassley, Jeremy Burchardt and Karen Sayer (eds.): Transforming the Countryside: The Electrification of Rural Britain (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017).

- 3. Mark Girouard, The Victorian Country House (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), see particularly 18-19.

- 4. Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880-1914 (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2008), especially chapter 3.

- 5. Hughes, 53-64.

- 6. Klaus Plitzner (ed.), Elektricität in der Geistesgeschichte (Bassum: GNT-Verlag, 1998).

- 7. Alain Beltran & Patrice Carré, La fée et la servante: la société française face à l’électricité XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Belin, 1991).

- 8. On the subject of ‘cultural persuaders’, see for example Philip Hammond, Climate Change and Post-Political Communication (London: Routledge, 2017) and Michael Goodman, Julie Doyle, and Nathan Farrell, ‘Practicing Everyday Climate Cultures; Understanding the Cultural Politics of Climate Change’, Special Edition of Nature Public Health Emergency Collection, 2020.

- 9. This theme of celebrity endorsement for environmental issues has been well-explored by a number of authors, most recently in the case of sustainable public transport. Paul Hanna, Joe Kantenbacher, Scott Cohen, Stefan Gossling, ‘Role model advocacy for sustainable transport’, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Volume 61, Part B, 2018, 373-382.

- 10. Ruth W. Sandwell (ed.), Powering Up Canada; The History of Power, Fuel and Energy from 1600 (Montreal: McGill-Queens Press, 2016).

- 11. Hughes, Networks of Power.

- 12. This topic has been explored in Michael Thad Allen and Gabrielle Hecht (eds.), Technologies of Power; Essays in Honour of Thomas Parke Hughes and Agatha Chipley Hughes (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2001) and Wiebe Bijker, Thomas P. Hughes and Trevor Pinch (eds.), The Social Construction of Technological Systems (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2012).

- 13. Mark Girouard, The Victorian Country House (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), 18-19.

- 14. Patrick Strange, ‘Early Electricity Supply in Britain: Chesterfield and Godalming,’ Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, vol. 126, n°9, 1979, 863–868.

- 15. Girouard, The Victorian Country House, 18.

- 16. Idem, 19, footnote 56.

- 17. Idem and Life in the English Country House (London: Yale University Press, 1978); Jill Franklin, The Gentleman’s Country House and its Plan (London: Routledge, 1981).

- 18. Such as Alice T. Friedman, ‘Architecture, Authority and the Female Gaze; Planning and Representation in the Early Modern Country House’, Assemblage, n° 18, August 1992 and Dana Arnold, The Georgian Country House; Architecture, Landscape and Society (Stroud: Sutton, 2003).

- 19. Hughes, Network of Power, 53-54.

- 20. Idem, 55-64, Jack Harris, ‘The electricity of Holborn’, New Scientist, 14 January 1982, 88-90.

- 21. Following the work of I.C. Byatt, The British Electrical Industry, 1875-1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979) 21-28. Hughes notes that electricity was comparatively more of a luxury in Britain than in the USA, Hughes, Networks of Power, 64. For discussion of the Grosvenor Gallery see below and Networks of Power, 97, 244.

- 22. Adrian Forty, Objects of Desire; Design and Society since 1750 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1986), 182-85.

- 23. For a detailed discussion of the histories of country house visiting see Peter Mandler, The Rise and Fall of the Stately Home (New Haven and London: Yale, 1999); Jocelyn Anderson, Touring and Publicizing England’s Country Houses in the Long Eighteenth Century (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

- 24. David Cannadine, The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy (London: Penguin, 2005).

- 25. Graeme Gooday, ‘Illuminating the Expert-Consumer Relationship in Domestic Electricity’ in A. Fyfe and B. Lightman (eds.) Science in the Marketplace: Nineteenth Century Sites and Experiences (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2007), 231-68. For a more traditional view that grants only agency to expert males, see Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

- 26. See Abigail Harrison Moore, ‘Agency, Ambivalence and the Women’s Guide to Powering Up the Home in England, 1870-1895’, in Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell (eds.), In a New Light; Histories of Women and Energy (Montreal: McGill Queens University Press, forthcoming 2021) for further discussion of the fear of ‘getting it wrong’ amongst middle-class Victorian women in England.

- 27. See for example Percy E. Scrutton, Electricity in Town and Country Houses (London: Archibald Constable and Co., 1898). While Scrutton does not provide costs for installing electric lighting, he does state that the annual running cost to light a country house with 200-250 electric lights, would be ‘under £150’; thus demonstrating how expensive electric lighting was at this time, 143.

- 28. See Graeme Gooday. Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880-1914 (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2008), Abigail Harrison Moore and Graeme Gooday, ‘Decorative Electricity: Standen and the Aesthetics of New Lighting Technologies in the Nineteenth Century Home’, Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 35, n°4, 2013, 363-83, Graeme Gooday and Abigail Harrison Moore, ‘True Ornament? The Art and Industry of Electric Lighting in the Home, 1889-1902’ in Kate Nichols, Rebecca Wade and Gabriel Williams, (eds.), Art Versus Industry? New Perspectives on Visual and Industrial Cultures in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015, 158-78) and our articles in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell, (eds.), ‘Off-Grid Empire: Rural Energy Consumption in Britain and the British Empire, 1850-1960’, Special Issue of The History of Retailing and Consumption, vol. 4, n° 1, 2018. We thank one of our referees for observations on the relative cost of electricity installation to the annual working wage.

- 29. Brian Bowers, ‘Scanning our Past from London; Advertising Electric Light’, Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 89, n°1, 2001, 116-8.

- 30. See Gooday, 2008.

- 31. Mrs. J.E.H. Gordon, Decorative Electricity (London, Sampson & Low, 1891) 14-16, 178.

- 32. See Graeme Gooday, ‘Women in energy engineering: changing roles and gender contexts in Britain, 1890-1934’, in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell (eds.), In a New Light; Histories of Women and Energy (Montreal: McGill Queens University Press, forthcoming 2021); Carroll Pursell, 'Domesticating modernity: the Electrical Association for Women, 1924–86', The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 32, n°1, 1999, 47-67.

- 33. Gooday, Domesticating and 2018.

- 34. Anne Clendinning, Demons of Domesticity; Women and the English Gas Industry 1889-1939 (London: Routledge, 2017).

- 35. See Philip Hammond, Climate Change and Post-Political Communication (London: Routledge, 2017) and Michael Goodman, Julie Doyle, and Nathan Farrell, ‘Practicing Everyday Climate Cultures; Understanding the Cultural Politics of Climate Change’, Special Edition of Nature Public Health Emergency Collection, 2020.

- 36. For Sir Coutts Lindsay, see Hughes, Networks of Power, 238-40. On Lady Lindsay as a daughter of the wealthy Rothschild family, see https://www.victorianresearch.org/atcl/show_author.php?aid=1634 and https://family.rothschildarchive.org/people/38-hannah-mayer-de-rothschi….

- 37. See Gooday, Domesticating.

- 38. Mrs Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (London: 1907), 56.

- 39. Lighting and Heating, Cooking and Power, Smoke Abatement Exhibition Catalogue (Glasgow: 1910), 59.

- 40. While we recognise that no women’s names appear in the advertisement, domestic decisions in this period were taken by both members of a married couple, but gendered convention meant that only the husband’s name would appear in print. On the impact of such conventions on historical assumptions about the active role of women in history see for example Deborah Cherry’s work on the difficulties faced by women in ‘the making of an author name’, Beyond the Frame; Feminism and Visual Culture; Britain 1850-1900 (London: Routledge, 2000), 157.

- 41. See, for example, Ben Marsden and Crosbie Smith, Engineering Empires; A Cultural History of Technology in Nineteenth Century Britain (London: Palgrave, 2005).

- 42. On this point see Eric Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968). He reminds us that in this period, the aristocracy still held much of the England’s wealth, necessary funds for technological transformation. They were little effected by industrialisation except for the better - ‘One important effect of this continuity…was that the rising business classes found a firm pattern of life waiting for them. Success brought no uncertainty so long as it was great enough to lift a man into the ranks of the upper class. He would become a ‘gentleman’, doubtless with a country house, perhaps eventually a knighthood or peerage, a seat in Parliament…his wife would become a ‘lady’, instructed in her duties by a multitude of handbooks on etiquette’, 80-82.

- 43. While Ruth Schwartz Cowan in More Work for Mother (New York: Basic Books, 1984) has argued for the US case that middle-class women were re-proletarianised by the rise of modern domestic technology, concurrent with the loss of servants, female authors in England in the 1870s and 80s proposed that women were or could be enfranchised by the ability to manage their homes and choose their interiors. For example Mrs H.R. Haweis in The Art of Decoration (London: Chatto and Windus, 1881) stated that ‘the design of your home is not just about aesthetics and function, but about spirituality and care’ (2) and while she expects a woman to employ a decorator, she commands that ‘His province is to help you in that mechanical part which you cannot do yourself. He may guide you; he must not subjugate you’ (350-1). See Harrison Moore (forthcoming 2021) for a longer discussion of women’s enfranchisement and interior design.

- 44. See Elizabeth Langland, Nobody’s Angels, Middle-class Women and Domestic Ideology in Victorian Culture (Ithaca and London; Cornell University Press, 1995) for an excellent analysis of such guides.

- 45. Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Macmillan, 1899).

- 46. Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New, 178; Gooday, Domesticating Electricity, 99, 108, 202, 225, 241, 261. On this subject see also Harold Platt, The Electric City: Energy and the Growth of the Chicago Area (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), and David Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990).

- 47. See for example, Langland, Nobody’s Angels; Catherine Hall, White, Male and Middle Class; Explorations in Feminism and History (London: Wiley, 1992) and Patricia Branca, Silent Sisterhood; Middle Class Women in the Victorian Home (Carnegie-Mellon Press, 1975).

- 48. See John Ruskin, ‘Of Queens Gardens’ in Sesame and Lillies (London: George Allen, 1895), 95-158.

- 49. K.D. Reynolds, Aristocratic Women and Political Society in Victorian Britain (Oxford; Clarendon, 1998), 28.

- 50. Idem, 21-28.

- 51. Girouard, 1978.

- 52. Reynolds, 28.

- 53. Idem, 28.

- 54. Idem, 28.

- 55. See J. Mordaunt Crook, The Rise of the Nouveaux Riches; Style and Status in Victorian and Edwardian Architecture (London: John Murray, 1999).

- 56. Reynolds, 17.

- 57. Mrs Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (London: Samuel Orchart Beeton, 1861).

- 58. Mrs Beeton’s book ran into multiple editions and there is debate about the role of her husband in the creation of the book and its life post her death. Samuel Beeton was certainly an ‘extremely sharp commercial operator with a talent for advertising and publicity’, who recognised the value of a woman being seen to guide women. For an excellent discussion of Mrs Beeton’s book see Margaret Beetham, ‘Good Taste and Sweet Ordering; Dining with Mrs Beeton’, Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 36, n° 2, 2008, 392.

- 59. Idem, 392.

- 60. On this point see Rachel Bowlby, Carried Away; The Invention of Modern Shopping (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) and Frank Trentmann (ed.), The Making of the Consumer: Knowledge, Power and Identity in the Modern World (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2006).

- 61. Mrs H. R. Haweis, The Art of Decoration (London: Chatto and Windus, 1881), 353.

- 62. See Briony McDonagh, Elite Women and the Agricultural Landscape, 1700-1830 (London: Taylor and Francis, 2018).

- 63. Frank Trentmann, Empire of Things (London: Penguin, 2016).

- 64. Frank Trentmann, ‘Getting to Grips with Energy: Fuel, Materiality and Daily Life’, editorial in Science Museum Group Journal, ‘The Material Culture of Energy’, Spring 2018, 8.

- 65. Sarah Strauss, Stephanie Rupp and Thomas Loue, Cultures of Energy (London: Routledge, 2013).

- 66. Mrs. George Cornwallis-West, The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill, by Mrs. George Cornwallis-West (New York: Century, 1908), 139.

- 67. Idem, 138.

- 68. For information on Lord Randolph Churchill’s activities in Parliament in relation to the promotion of electric light in the House of Commons, see https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1883/apr/17/the-hous… and this related debate in 1883 about the House of Commons electrification: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1883-05-10/debates/639fff12-fd31-….

- 69. Cornwallis-West, 138-9. The correspondence on this issue between Lady Churchill and R.E.B. Crompton is dated 19-21 January 1885. See Churchill papers at Churchill College, Cambridge, CHAT 28/99/31-33.

- 70. R.E. Crompton, Reminiscences (London: Constable Co 1928), 109.

- 71. Idem, 110.

- 72. See Gooday, Domesticating; Mrs J.E.H. Gordon, Decorative Electricity, 2nd edition, 1892, iii-iv.

- 73. Carroll Pursell, ‘”Am I a Lady or an Engineer?” The Origins of the Women’s Engineering Society in Britain, 1918-40’, Technology and Culture, vol. 34, n° 1, Jan 1993, 78-97.