Resource Imperialism and Resistance: Labour, Security and Social Reproduction after Iranian Oil Nationalisation

SOAS

@mattinbiglari

mb125[at]soas.ac.uk

London School of Economics

@rowenarazak

rowena.razak[at]googlemail. com

The Iranian oil nationalisation crisis, which ended in the coup that overthrew nationalist prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, is well known. An international Consortium of the world’s major oil companies replaced the dominance of the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, but relatively little is known about the history of Iranian oil and its workers after 1953. Even after the coup, tensions continued between workers and management, leading to corporate strategies to maintain order over social reproduction, including repression and social engineering. Meanwhile, even before the Suez crisis, the British government still maintained its imperial vision over the Persian Gulf and considered the refinery city of Abadan as an opportunity to re-enforce its prestige. This paper examines how the Consortium addressed the exigencies of labour’s social reproduction in relation to corporate interests and ongoing British energy imperialism. By pointing to the resistance from the local population across oil operating areas, it argues that the Consortium and British government ultimately failed to fully control oil operations, such that not even automation could supplant the human in oil operations.

Introduction

Since the early twentieth century, oil has been a natural resource of utmost geostrategic importance for Western powers and a key reason for militarism, occupation and war – a subject continuing to generate new scholarly interest.1 Conversely, it is because of this importance that oil has been central to resource nationalism across the Global South, linking sovereignty over oil to decolonisation.2 Indeed, in the decades following the Second World War, several oil-producing states altered the global balance of power through OPEC and the control of oil supply.3 Thus, there was a tension between imperialism and oil-producing states, and one that was periodically resolved through imperialist intervention.

Perhaps the most famous instance of this was the 1953 coup in Iran, organised by MI6 and the CIA to depose Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq and reverse the country’s nationalisation of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) in 1951.4 As a result, foreign control over the country’s oil operations resumed in 1954 under the auspices of the Consortium, made up of eight of the world’s major oil corporations: AIOC, Shell, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Esso), Standard Oil of California (Socal), Socony-Vacuum, Texaco, Gulf, and Compagnie Française des Pétroles (CFP). The 1954 Consortium agreement gave ownership of oil to the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) but assigned de facto management of operations to the Consortium. Further to this, was the British government’s desire and drive to ensure that Britain would have a controlling share of the arrangement. On the surface, then, imperialist intervention had crushed resource nationalism and secured energy security for the West. In the subsequent decades of the Cold War, the US maintained security over the flow of oil through financial, diplomatic and military support to authoritarian leaders in oil-producing states, especially in the Gulf, where most of the world’s oil was produced.5 While this created some tensions with Britain, even London acknowledged the new positioning of the US in the region, especially in order to secure flow of oil from the Gulf for the necessary energy for economic growth in the West following the Second World War.6

But this only tells half the story. As the burgeoning field of energy history shows, ‘energy’ is an abstraction that conceals how the specific means of its production are imbricated in politics.7 Consider, for instance, the role of coal in enabling colonial expansion, or in the production of the modern technocratic state.8 Similarly, as Timothy Mitchell argues in critique of rentier theory, we must look to the political arrangements built into the oil industry before the finished product and revenue it generates.9 For example, the natural properties of oil allowed Western governments to find alternative sources of energy to coal in the early twentieth century, thereby being less vulnerable to mass strike action and workers’ resistance. Oil’s liquid and relatively light nature allowed for it to be transported by pipelines and oil tankers, in contrast to coal’s transportation on railways, which could be more easily shut down through general strikes.10 Thus, the expansion of energy consumption was possible through interference into that ‘hidden abode of production’ – through controlling labour.11 Indeed, the very concept of ‘energy’ was born in mid-nineteenth century Europe to signify the world being put to work.12 Furthermore, in post-war British imperial thinking, interest in industrial politics, particularly in Iran, was packaged as part of a reformist agenda, spearheaded by Labour Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin as another means by which Britain could maintain control in the south of Iran and prolong its influence over oil matters.

As social historians of the Iranian oil industry have argued, labour activism consistently shaped oil operations and wider national politics across the twentieth century.13 Oil workers were pivotal in the Iranian Revolution 1978-79 through a general strike that crippled the country’s economy.14 Similarly, oil workers’ activism in the early decades of the industry forced the AIOC to embark on a series of disciplinary, social engineering and public relations policies to manage the ‘human factor’ of operations.15 And it was labour that helped give rise to resource nationalism and anti-imperialist mobilisation throughout the oil operating areas of Khuzestan province in the late 1940s, making nationalisation possible in 1951.16

Therefore, focusing on the 1953 coup outside of the industry takes for granted that the production of oil would be free from disruption. It does not answer a crucial question, and one that this article will address: how could foreign control over oil operations continue in 1954 in a context in which it had been fiercely opposed and banished 1951, especially by labour? In other words, how did the Consortium, as well as the British government, establish control over operations in the quest to ensure the frictionless flow of oil from the wellhead to the consumer, and what political arrangements did it pursue?

Answering these questions also requires one to look beyond the sphere of production alone, and to consider that of social reproduction, where workers were born, raised, nourished, trained, and ultimately sustained on a daily basis. As feminist Marxists have long argued, social reproduction requires work to produce a labour force – historically performed mostly by women – but which is not formally recognised as labour itself. Not only does this work encompass the biological reproduction of future workers, but also the ‘various kinds of work – mental, manual, and emotional – aimed at providing the historically and socially, as well as biologically, defined care necessary to maintain existing life and to reproduce the next generation’.17 At the same time, social reproduction is undertaken by states or corporations through the education and training required to produce a skilled workforce.18 Scholarship on Fordism has also shown how large corporations engaged in welfare paternalism during the interwar period to control workers’ lives beyond the workplace, shaping the sphere of social reproduction to make workers more productive.19

The centre of the Iranian oil industry was the Abadan refinery in south-west Iran, which was then the world’s largest. But it also happened to be situated in the middle of a city of over two hundred thousand people who were greatly dependent on the oil industry. Like other parts of the Gulf, oil had constituted an urban modernity that exceeded the designs and control of either oil companies or ‘the state’ on the micro-level.20 In particular, AIOC had been drawn into the city’s quotidian life despite consistently seeking to disentangle its technical operations from ‘politics’. Ultimately, the failure of the company to ensure the adequate social reproduction of its workforce solidified its reputation as a colonial presence and fuelled the nationalisation movement by the late 1940s.21 How, then, would the Consortium deal with this fundamental issue?

Following the recent turn towards labour in the history of oil, this article contends that such an enquiry requires close attention to corporate practices and lived experiences on the ground.22 Moreover, it builds on the insights of energy history and the energy humanities, especially relating to oil, to open the ‘black box’ through which it is seemingly abstracted and made ubiquitous.23 It does so by making use of documents from the BP Archive and state archives in the US, UK and Iran, as well as personal papers, oral histories, newspapers and magazines from the time.

It first demonstrates how the Consortium faced local opposition upon assuming control of oil operations in Abadan, and how it attributed this to a crisis of social reproduction inherited from the pre-nationalisation era. The article will then highlight how the Consortium responded to local resistance, before outlining the main measures pursued to mitigate it, such as downsizing, securitisation and social engineering. It argues that although the Consortium was able to avert mass mobilisation on the scale of the nationalisation movement, it was still beholden to the ‘human factor’ of operations and was never able to escape the exigencies of social reproduction. Hence, oil workers in Iran continued to play a prominent role in wider politics in subsequent decades, despite contemporary trends towards automation and post-Fordism in many other contexts across the global oil industry. So pervasive was this human factor that not even automation could be fully introduced to supplant the human labourer, at a time when oil companies in the West were doing so to disempower labour movements in the oil industry.24

This article will also demonstrate that the British government in London was keen to resume its presence and power that it wielded before 1951. Anthony Eden, in his capacity as foreign secretary and later prime minister, was keen to push for this: firstly, by establishing good relations with Tehran; and secondly, by keeping a close eye on negotiations for the Consortium. After all, it was under his purview as foreign secretary in Winston Churchill’s wartime cabinet that British control over Iranian oil and presence in Iran was tightened. Indeed, his particularly hawkish stance towards nationalism would later erupt into war after Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in July 1956. Barely five years before, events in Iran humiliated imperial pride, leaving a strong mark on British strategic thinking. The NIOC was regarded as incapable while Iranians as troublesome, and worse, could inspire other uprisings against Britain. The 1953 coup therefore removed a threat and presented an opportunity to reassert British control not only in the country but in the region.

The role played by London was therefore crucial in ensuring that British companies held a key position in the Consortium. Despite the multi-national nature of the agreement, the British government were keen to push for the positions of AIOC/BP and Shell, of which Britain had a majority say. This maintained British imperial designs and upheld central control over Iranian oil. Nonetheless, the British government was subject to domestic industrial shifts and limited by financial constraints. As such, by interweaving British governmental policy, another layer of insight can be revealed about how British imperial designs permeated Consortium attitude towards Iranian oil and oil workers.

Back to topThe Arrival of the Consortium and Local Opposition

‘Dear fellow countrymen. Today Abadan is turning from darkness into light. The wheels of this great industrial machine, which is unique in the world, commence once again the operation of refining Khuzistan oil. The energy and activity essential to your life is again taking the place of silence and activity. The oil wells which were shut down are started up again and the pipes which connect them to the refinery and ports will again convey this rich and valuable liquid from the depths of the earth to the refineries and storage tanks. The wealth resulting from the proceeds of this liquid will, like blood running into veins, pervade the whole life of this country. The circulation of this wealth must result in the enrichment and prosperity of the country and the enhancement of your comfort and well-being. It must wipe out misery and poverty as a flood washes away dirt and pollution’.

These were the words of Iran’s Minister of Finance, Dr Ali Amini, when addressing oil workers in Abadan as the Consortium began operations on 30 October 1954. The workers of Abadan, Amini continued, had claimed the refinery for the nation and protected it from damage over the past three years. But now, Amini stressed, it was time for workers to pass responsibility over the refinery to the Consortium and learn from its experts and ‘respect their knowledge’.25

Relations between newly arrived foreign staff and Iranian employees quickly became tense. After little more than a year since the Consortium started operating there were already widespread reports of Iranian employees’ resistance to new management. In December 1955, the US consulate at Khorramshahr reported that the current situation was such that ‘a labourer who has committed a wrong is encouraged to attempt to defy’ the Consortium, ‘thus endangering labor discipline and to that extent, threatening the whole objective of the oil agreement’. This had been shown in in two notable cases that occurred in the refinery. On one occasion, two Iranian workers attacked the refinery’s timekeepers, while on another one, an Iranian welder who had been ordered to undertake a new kind of work approached his British supervisor and ‘drew a knife and threatened to kill him’ unless he was allowed to return to his welding job’; in both cases, the Iranians workers involved were immediately dismissed.26 As Maral Jefroudi shows in the most comprehensive social history of the oil industry in the immediate post-nationalisation period, there was also a series of smaller-scale work stoppages across oil operations in 1955-57.27 According to one US diplomat in Khorramshahr, this resistance resulted from ‘the general intense dislike of foreign management’. This had been fuelled by years of ‘promises by ignorant demagogues’ in the pre- and post-nationalisation years, which many workers still believed could be carried out ‘if management were not so “greedy”’.28

But from the perspective of the Consortium, there was one foundational reason underlying this discontent: a large labour surplus. Already in December 1955 the managing director of the Consortium, L. E. J. Brouwer, complained that there were 30,000 people employed by the refinery alone, when its ‘efficient operation’ only required 12,000.29 This surplus was commonly attributed to the workers staying in their jobs for too long. In June 1958 the US embassy reported that in the Iranian oil industry ‘nobody quits and few retire…. [t]he obsession with the need to stay on the job is a recently developed rather than traditional attitude’, citing the fact that in 1948 turnover of wage earners was 21.3% but dropped to 7% in 1950-51 and to less than one per cent every year after 1953. This, it was stressed, seemed to constitute a ‘sociological paradox’: ‘[n]early half of the workers are of semi-Nomadic tribal origin, but it appears that the sheep and goat herders, once accustomed to the habits and amenities of a sedentary life, are unwilling to go back to their sheep and goats on a mountainside. In an area where no alternative means of employment is available, they stay with their Consortium employers’.30

Consequently, there was an even greater problem in Abadan’s growing unemployment. In a highly confidential white paper written by the Consortium’s manager of employee relations addressed to the refinery general manager on 31 December 1956, the rising number of unemployed adults was described as the issue that ‘many consider to be the single greatest problem to be faced by the two operating companies in the near future’.31 There were currently 80,023 children in company areas, meaning that by 1960 there were estimated to be at least 50,000 unemployed adults in Abadan. Furthermore, they were ‘too-well educated to enable the problem to be easily solved’ as now they could not get employment commensurate with their education level and there were no other local industries to absorb them.32 This was the legacy of AIOC, which had extensive vocational training and primary/kindergarten education schemes since the 1930s, with the twin aims of producing future employees and socialising the children of employees, respectively. The company’s training schemes were exemplified by the Artisan Training Shop (est. 1933) and Abadan Technical Institute (est. 1939), the latter being the first in the country to offer a bachelor degree programme in Petroleum Technology.33

The white paper concluded that Abadan now demonstrated the dangers of overpopulation:

‘The development of a barren piece of land populated only by scattered agricultural locals until there exists a teeming population crowded into a semi-advanced “milieu” which requires water, electricity, a police force and all of the features of a highly organized natural community really takes little more than time and a lack of foresight with regard to human reproduction and certain basic business principles. Unfortunately hundreds of businesses all over the world are carefully constructing the traps which will sooner or later engulf them’.34

Incidentally, such corporate concerns were not new in Abadan. Since the 1920s, the AIOC had intervened in the town through several urban planning and measures and paternalist welfare schemes to social engineer the population and produce a productive, healthy workforce.35 However, these had largely failed to bring the ‘human factor’ under control, as urban spaces became key sites of political mobilisation against the company by the 1940s, exemplified by the 1946 general strike. AIOC foreshadowed the Consortium’s later assessments in regularly attributing this unrest to a crisis of social reproduction. For example, director J.A. Jameson admitted in 1938 that the throughput of the refinery was ‘not only a matter of plant capacity’, but also ‘a social problem influenced by living conditions in Abadan Town and the surrounding villages’, and that ‘from a labour point of view’, Abadan may ‘have reached saturation point’.36 Yet for the Consortium, this problem was amplified by the growth of the city’s population, which increased from 120,000 in 1943 to 226,000 in 1956.37

As well as migration, a chief reason for this increase was supposedly an excess of social reproduction, which brought with it dangerous consequences. Now, according to the Consortium’s white paper, employees had ‘reproduced themselves three or four times’ and their children were becoming adults and a potential source of disorder. ‘There is probably nothing more insidious’, the report continued, ‘than a large group of idle educated adults in this part of the world’, resulting in increasing rates of theft and burglaries. Moreover, it was fertile ground for political extremism: ‘we are encouraging crime, communism, bitterness and even revolt’. Thus, ‘serious politico-economic crises’ were predicted for the near future unless remedial action was taken.38

Back to topMitigating the Crisis of Social Reproduction

The Consortium pursued three paths to deal with this situation. First was a program of downsizing, comprising several measures. It continued the freeze on recruitment that had been in place since nationalisation in 1951. In 1957 it also embarked on a plan of voluntary retirement for 10,000 workers, especially those deemed to be overaged and disabled.39 A far more prominent part of the plan was absorbing ‘surplus workers’ in the many development projects across the country. Already by July 1955 the Consortium was co-ordinating with two British firms to use surplus labour in development projects they were working on: the construction of the southern half of a pipeline from Ahwaz to Tehran and the the paving of 6,000km of roads across the country.40 The Consortium also diverted surplus labour internally to ‘marginal work’ rather than ‘cluttering up the petroleum production job’. It was a major hope, according to the US Embassy, that the Consortium could siphon off workers through the industrialisation of Khuzestan, especially the Khuzestan Development Service’s plans to grow a petrochemicals industry in Ahwaz.41 Another scheme was the development of Khark Island into a new loading port, where the company sent 350 workers in 1957 and threatened them with discharge if refusing.42 These early efforts laid the foundations for a massive downsizing of workforce in 1960s.43 In this view, the levels of biological reproduction were too high for the orderly maintenance of broader social reproduction.

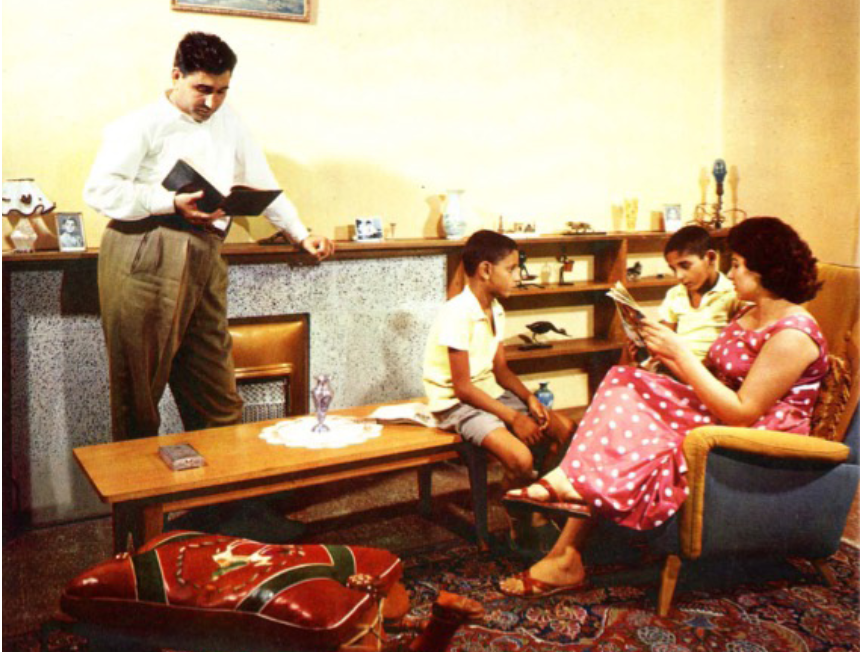

The second path pursued was shaping the remaining workforce through disciplinary mechanisms and social engineering. Consortium management sought to improve industrial relations mechanisms and welfare schemes early on, introducing a supervisory training program in the summer of 1955 to develop a corps of loyal foremen who could ‘assimilate and pass on a certain amount of management’s viewpoint’. In addition, several bulletin boards had been installed at various strategic points in the refinery to ‘habituate’ employees to reading special notices from management and spreading these by word of mouth.44 The company also published pamphlets for employees to stress the importance of discipline beyond work. For example, workers were reminded that ‘[g]ood time keeping is one of the vital steps to efficiency’ and to even avoid being fifteen minutes late for a social meeting.45 They were told to not ‘leave taps running’ and to ‘use less drinking water’.46 They were also were encouraged to ‘Be Tidy Minded’, not to litter, and even about how they should best tend to their gardens.47

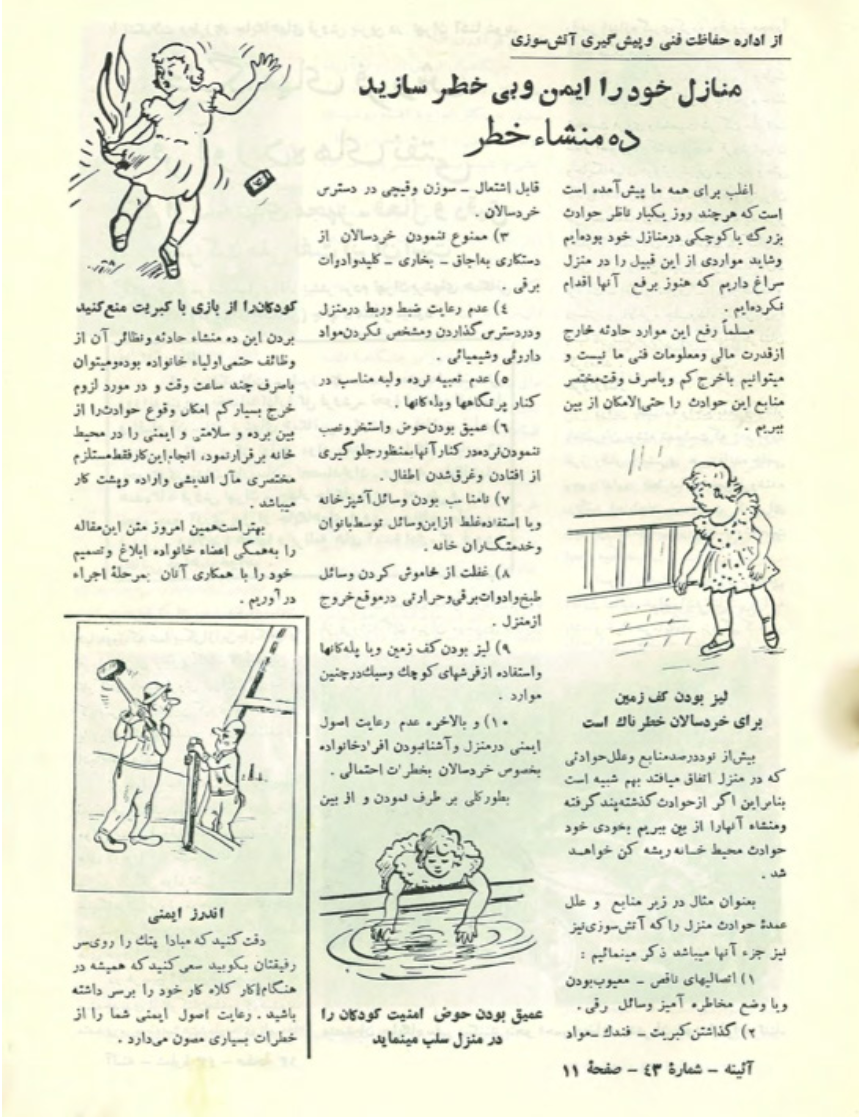

In the emphasis on the home as a vehicle for discipline, women were singled out as playing an especially important role. To be sure, women were now more visible as workers in the oil industry: although exact figures are hard to come by, they were now featured in Consortium publications more frequently as typists, stenographers and secretaries. However, they were still expected to be chiefly responsible for maintaining order in the home through housekeeping and socialising children. For example, in a June 1961 article in the Consortium’s Persian-language publication, Aineh, female readers were urged to keep the home clean and tidy, to be responsible for timekeeping, and to teach children about cleaning from an early age, ending with a direct appeal about the benefits of doing so both for the home and the workplace: ‘Madam, by abiding by tidiness and timekeeping, you can be an orderly and dutiful woman in the office, and your home and children will shine from cleanliness’.48 As was the case in other parts of the world’s oil frontier, the company heavily relied on women’s reproductive labour in ensuring a productive, healthy workforce.49

Third, when the above measures did not work, the company worked with Iranian authorities to quell any resistance. Following the 1953 coup, the Iranian government took a more active role in clamping down on political dissent through martial law, especially targeting the Tudeh Party, who had played a leading role in the labour movement in the 1946 general strike and in 1951-53.50 Already in October 1954 labour unrest was described as having been ‘moderate’ since nationalisation, ‘largely due to reasonably strict Governmental security’.51

Security became more advanced and repressive through the institution of SAVAK in 1957, such that even underground activities were foiled. Although the British Labour Attaché expressed concern about how the Iranian government would implement change in the labour force, there was no explicit objection to strong methods, suggesting either a reluctance to interfere or more sinisterly, an implicit approval of suppression.52 For instance, in June 1957, SAVAK and NIOC’s own security forces uncovered the plan of five individuals believed to be Tudeh members to commit robbery and arson on several installations in the Abadan refinery; NIOC had even planted two spies in the group.53 Meanwhile, there was a zero-tolerance policy towards any employees who were openly critical of NIOC or the Consortium. For example, in 1958 a NIOC member of staff was dismissed because he had published several articles in newspapers that attacked the Consortium.54 SAVAK’s files indicate that there was a network of informants in the refinery and training centres such as the Abadan Institute of Technology, and that SAVAK largely controlled trade union activity.55

Back to topThe British Government and Iranian Oil After 1953

Concerns surrounding the new environment the Consortium found itself reflected the British government’s own anxieties surrounding its position in Iran. The removal of Mosaddeq in a coup was a relief to the British government. The nationalisation of Iranian oil had not only challenged British control over this resource but also Britain’s imperial presence in Iran. The Iranian takeover had humiliated the British government as well as the AIOC, with photos and newsreels of company personnel leaving shown worldwide. The presence of the company throughout the country was erased, with signboards removed and company symbols replaced by the NIOC.56 The August 1953 coup was thus an opportunity for Britain and the AIOC to restore some of their lost status in Iran. Indeed, AIOC chairman William Fraser insisted that full control should be re-established as ‘British prestige in the Middle East was at stake and we could not afford to have a consortium forced on us.’57 Clearly what happened with regards to Iranian oil had implications beyond the Persian Gulf. Even when the idea of a consortium was accepted, Britain and British oil companies needed to have the highest share.58

British interest in Iranian oil was tied to other issues. In his work on the Consortium era, Steven Galpern revealed how the British government was anxious regarding the methods of payment and wanted to prioritise the use of sterling. The flow of currency to Britain was a key factor in negotiations with other oil companies and the Iranian government. Ways in which the government could ensure this was by insisting that operation companies needed to be registered in the UK while the British Treasury pushed for policies that protected the country’s balance of payments.59 From Eden’s point of view, this economic aspect of the Consortium’s new position in Iran was to have important implications. He revealed that:

It is very much in our economic and political interests to get a firm and early foothold in the expanding Persian market… An improvement of our trading position will strengthen our political and cultural influence.60

Eden clearly saw an opportunity through the Consortium to re-establish presence in the country and to restore some of imperial prestige. When his Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Selwyn Lloyd deputised for Eden, he perpetuated this line of thinking and called for the “strengthening of the traditional friendship between the United Kingdom and Persia.”61 The feeling appeared mutual when Iranian ambassador to Britain Ali Soheili expressed confidence in the bilateral relationship and sought Eden’s advice regarding Iran’s geopolitical strategy.62 This echoed immediate post-war British policy towards Iran which called for a stable government in Tehran that relied on British advice and protected Britain’s primary interest: access to oil.63

In this regard, even attitude towards Iran and oil was imperial in nature. This may not seem surprising given the colonial mentality that permeated the negotiations for the Consortium. The British government did not regard Iran as an equal partner, even though it took care not to be regarded as imperialist.64 Churchill’s Conservative government, much like the Labour government before, wanted to maintain the integrity of the empire. Despite the loss of the Indian subcontinent, British control was still present from Egypt to Brunei. Although Iran was never formally colonised, it was still subject to British imperial interests and was a key component of British strategy towards the Soviet Union. This was apparent during the British occupation of Iran during the Second World War. Although Iranian sovereignty was protected by agreement, in practice, the British exercised significant political and military power through the British Legation and the army. However, it was in Abadan that British control was noticeable, especially with regards to workers. An Order-in-Council was introduced to restrict movement, legalise forced labour and ensure full co-operation.65 The war and occupation set an important precedent for the British government in terms of treatment towards oil workers.

Reminiscent of Britain’s wartime role, the Consortium era presented a renewed opportunity for London to be involved in important oil decisions.66 This is not to say that the British government was oblivious to the suspicion such involvement would create, and there were concerns that Iran would regard BP as “little more than a sub-department if the Foreign Office.”67 As such, interference was dealt with carefully. During negotiations over crude oil in the Middle East, the British government was concerned that BP was making decisions without consulting them. The Ministry of Power posited that the company did not have a holistic view when it came to oil and blamed them for ignoring the political implications of cutting crude oil prices on relations with countries such as Iran and Venezuela. Considering these concerns, the minister himself Lord Percy Mills explicitly asked for the company to consult them for future decisions.68 This led to a discussion regarding the relationship between the government and BP, and if the government should use its share in the company to weigh in on company policies. While some in the cabinet were reticent about being too involved, especially in the post-Suez climate, the Minister of State for Foreign Affairs David Ormsby-Gore agreed with Mills about being involved in BP decision-making, though cautioned that such consultations should be informal.69 Ultimately, this was agreed upon and informal advice would be given by the government over decisions that had major political impact.70 This also extended to BP’s social and wages policy.71

The British government’s mentality towards international workers’ rights appeared to have shifted since the occupation period. For instance, there were efforts to correct imbalances in pay between British and non-British employees abroad.72 Nonetheless, in the immediate post-1953 era, the British government faced rising prices of goods and the threat of national strikes. The Minister of Labour and National Service Walter Monckton highlighted “a sharpening of conflict and a deterioration in the climate of industrial relations which may have significant political implications.”73 Strikes affected relations between government and trade unions, but also disturbed the flow of goods.74 This placed pressure on how London viewed labour matters, caught between the intention to improve workers’ conditions and the need to avoid disruptions.

When Eden became Prime Minister, he dealt with nationalist fervour in the Middle East through military means. Since the end of the Second World War, London had been reluctant to use overt military force to intervene, avoiding it during the 1946 oil strikes and even when Iranian oil was nationalised in 1951. Yet Eden decided to opt for military action to counter the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, with disastrous consequences not only for Eden’s premiership but also British international politics.75 His successor Harold Macmillan, who served as Housing Minister and Defence Minister in the first years of the Consortium, focused on rebuilding the relationship with the US but also Britain’s unstable footing in the region.76 Tensions felt in Iran reached Aden, where BP had also established a refinery as part of extensions to Abadan. The British colony in the Yemeni peninsula was more than a symbol of Britain’s imperial presence in the Persian Gulf, it was a military base for its Middle Eastern force and oil operations. The refinery was prone to strikes, revealing the instability Britain faced when it came to oil workers.77

Back to topThe Renewal of Activism in Khuzestan

The same instability applied to Abadan. Although the Consortium was able to prevent overt political mobilisation on the scale of the pre-nationalisation period, its measures to mitigate the crisis of social reproduction had not curtailed dissent altogether. One grievance commonly expressed by oil workers was dissatisfaction about barriers to promotion. In 1957 workers were complaining about barriers to promotion or being transferred to other work where their skills were not utilised, and there was a widespread feeling that ‘the choice jobs in the industry go to foreigners, that insufficient attention is given to training Iranians to take over key positions, and that foreigners are paid higher salaries’.78 This is also the view of former Consortium employee Manuchehr Parsa, who explains how there was an employee grade system out of twenty and that it was ‘very difficult’ for Iranians to reach a higher grade than twelve. This was even though Iranian workers often found solutions to problems that their foreign superiors could not: for example, Parsa recalls how he was able to solve a problem with the SO2 plant when his Dutch manager had already sent several experts to do this but to no avail.79 The Consortium’s barriers to promotion for Iranian workers became so contentious that in April 1959, workers sent a petition to the Senate to complain about how it kept them as unskilled labourers.80

Likewise, when Abbas Mas’udi, senator and editor of the country’s leading newspaper, Ettela’at, visited Abadan in January 1959, members of NIOC employee relations department complained to him that the future of the Iranian Oil Industry was ‘in great danger’ because the Consortium and NIOC had paid no attention to Iranian employees and treated overseas staff much better.81 This highlighted how ‘Iranianisation’ – the gradual replacement of foreign technicians and managers by Iranians – had been not realised, despite being one of the central demands of oil workers in the nationalisation movement.82 Although Mas’udi had been a champion of Iranianisation in the pre-nationalisation period, now he rebuked these demands and defended the needs for foreign experts.

In part, this was perhaps a product of the Consortium’s attempts to monopolise oil expertise, much like AIOC in the pre-nationalisation period. The 1954 Consortium agreement assigned management of ‘basic’ operations to the Consortium and ‘non-basic’ operations to NIOC: the Consortium would control matters relating to the extraction, production, processing and transporting of oil, and NIOC would be responsible for all ancillary activities such as housing, leisure and training. This exclusion allowed the Consortium to claim Iranians lacked the necessary expertise to manage ‘basic’ operations. For example, like AIOC, it cited safety and accidents as highlighting Iranians’ incompetence: after a fire in the refinery distillation area on 13 July 1959 killed six employees, the refinery general manager asserted that the accident was proof that Iranians were unable to operate the refinery. However, Iranians blamed the Consortium’s failure to institute an adequate training program and a promotion policy that would give Iranians an incentive for self-improvement.83 Indeed, in April 1958 the Abadan branch of the Association of Iranian Engineers condemned the Consortium for failing to further the training of Iranian engineers.84

These complaints reflected the Consortium’s withdrawal from directly training Iranians into oil experts. In 1956 it invited the US university Lafayette College to conduct a survey of the Abadan Technical Institute. The subsequent findings suggested that the institute be disconnected from the oil industry directly and instead be converted into a general engineering college to supplement Tehran University in producing practical engineers to aid Iran’s various development projects.85 Subsequently, the school was remodelled as the Abadan Institute of Technology (AIT) and administered by Lafayette College. While it still offered the specialist programme of Petroleum Engineering, this was only one among many engineering courses taught (although it was to revert to a specialist petroleum engineering college under Iranian management in 1967). By 1960, the Consortium had passed on responsibility for all training – including the AIT – to NIOC as a ‘non-basic’ operation, as had been originally planned in the Consortium agreement. In doing so, it reinforced a barrier to promotion for Iranians by externalising training as separate from ‘basic’ operations, removed from the technical matters of refining and extraction, thereby justifying claims of Iranians’ supposed ‘lack’ of expertise.

This was but one part of the Consortium’s wider retreat from investment in social reproduction. Although the Consortium agreement gave responsibility to NIOC for all non-basic operations such as housing, infrastructure, healthcare and food subsidies, in practice it did not relinquish control over these immediately. As such, there was no serious housing construction programme in the first years of operations, and workers started petitioning the Iranian government about housing shortages.86 One former employee even recalls how this was the main issue that workers raised with Prime Minister Eqbal when he visited Abadan in June 1959.87 Moreover, the lack of investment in infrastructure became a major grievance with local residents, who sent a petition to parliament in 1959 about water and electricity shortages. In it they claimed that the severe heat in Abadan meant the city should have better infrastructural supply than Tehran, but that it was being neglected in favour of the capital.88

US diplomatic reports indicated that Consortium personnel viewed their General Manager in Iran, chairman Koos Scholtens as ‘oblivious to the social problems associated with the refinery’ and the company’s ‘paternalistic responsibilities’.89 For instance, in 1958 workers demanded improvement of minimum wage basket, which included subsidised essential food items (which was also one of the labour movement’s main demands), but the Consortium refused to negotiate based on the assertion that there was a high number of ‘redundant’ workers.90 Despite the Consortium’s willingness to intervene in social reproduction through discipline, then, it preferred to deflect responsibilities of provisioning for social reproduction to the Iranian government. Rather, the main policy pursued to deal with the crisis of social reproduction was to reduce, not ‘improve’, Abadan’s population.

As a result, and despite severe repression, there was renewed labour activism in the oil industry by the late 1950s. In 1957 there were several strikes in oil-producing areas like Agha Jari and Masjed Soleyman over the cost of living and low pay, which workers linked to barriers to promotion, and strikes followed in Khark and Bandar Mahshahr in 1958-59.91 The British Labour Attaché in Tehran noted discontent among the Consortium’s workers, arising from redeployment of workers from the refinery in Abadan to construction work or to work on Khark Island. This led to a brief strike in April 1958 where workers expressed upset about the transfer, a reduction in basic pay, the quality of food supplies and living conditions on the island.92 Concerns of their future and job security permeated among workers, exasperated by rumours about large-scale dismissals which arose directly from the Consortium’s poor policies toward employment.93 This also took place within a wider national context of labour unrest: in the summer of 1959, industrial unrest was witnessed all over the country, in Tehran, Isfahan and Shiraz. There were unsettling disputes between workers and the local authorities, with the former ready to disown their representatives.94

As Jefroudi argues, although the mobilisations in the oil industry at this time were small-scale, they helped apply pressure on the Iranian government to institute the 1959 Labour Law and embark on a pro-labour discourse throughout the ‘long 1960s’.95 Although this policy aimed to contain and control the labour movement, it also provided space for collective bargaining with the state, hence why labour activism continued in the oil industry in the 1960s and 1970s. Through labour, then, the Consortium had become more embroiled in politics. An early warning about this came from one US diplomat in 1955, who wrote that there was a danger the refinery would soon be running at a financial loss and operating ‘for political reasons alone’.96

At this moment, one solution appeared that offered the hope of securing control over labour in the oil industry: automation. By the late 1950s and early 1960s computerisation of refineries was allowing oil companies and government to operate without much disruption from labour activism.97 In Abadan, there had been small-scale automation since the late 1940s, which the Iranian intellectual Al-e Ahmad recognised upon his visits as a political decision to reduce the power of labour.98 Nevertheless, the political significance of the refinery, and the large local population dependent on it, meant that it could not easily be automated. The Consortium had inherited a relatively large workforce from the pre-nationalisation era in the refinery itself and in ancillary operations, including medical staff, company storekeepers, club personnel and construction workers. In 1958 the labour ratio at Abadan refinery was 200 employees per 1,000 barrels of throughput, compared to five employees per thousand barrels in the most efficient refinery in the US and thirty employees per thousand barrels in the least efficient refinery in the US.99 Indeed, in 1956 there were reportedly 160,000 people in Abadan who were directly dependent on the Consortium for their livelihood.100 In addition, much of the refinery’s plant was built in the interwar period and 1940s and so was difficult to update: it was even described as ‘an old, almost obsolescent, installation with very little mechanization’.101 Ultimately, given the cheapness of this labour and the political and social desirability of providing employment, management had decided that automation would not be desirable. Nor was the option of building a new and remote refinery away from local populations. Like AIOC previously, the Consortium could never escape the demands of social reproduction.

At the same time, the proliferation of refineries around the world from the 1950s onwards reduced the importance of the Abadan refinery in the global oil industry. In line with rising oil consumption (the 1950s was the decade that saw global oil consumption rise above coal consumption), many new refineries were built closer to sites of consumption, especially in Europe. During the 1950s, refining capacity in Western Europe increased approximately five-fold.102 But this trend was also due to the wider context of decolonisation in the world: oil companies sought to become less vulnerable to the political instability of nationalism and avoid another Abadan, while newly created postcolonial states had aspirations to nationalise oil to secure their own market supply while creating the symbolic effect of progress; thus a series of joint ventures were created to build new refineries across the world.103 Indeed, the Aden refinery built in 1954, was a source of tensions between the Yemeni population and BP. In 1959, there were eighty-four strikes, and issues there were tied in with wider concerns regarding Britain’s position in the region.104 Furthermore, increased deadweight capacity and speed of tankers and the building of new pipeline networks, especially in Europe, made it much more economical to transport crude.105 Finally, the new refineries that were being built possessed all the most up-to-date processing plant possessed by Abadan and more. BP quickly introduced identical Kellogg catalytic crackers to Abadan’s in its Llandarcy, Grangemouth and Kent refineries in 1953. The new secondary process of ‘platforming’, which was patented in 1947 and converted low-octane gasoline into high-octane gasoline, was introduced into a series of Shell’s refineries in the early 1950s.106 All of these developments allowed for greater flexibility of oil production, refining and transportation that ultimately reduced the capacity of a single refinery to act as a bottleneck in the global oil industry, although oil workers did not have the capacity to disrupt the oil industry on a local level.107 As such, nationalising an oil refinery, as was the case in Iran in 1951, was less disruptive than before to the flow of oil and to global politics.

Back to topConclusion

Abadan continued to play an important role in the politics of Iran. The presence of an usually large workforce in the Iranian oil industry, and the lack of automation in the Abadan refinery, meant that oil workers still possessed much power. Hence, oil workers could still play a central role in the 1978-79 revolution. The irony was that for all the talk about the arrival of post-Fordism at the end of the 1970s, and especially a ‘new working class’ of knowledge workers in refineries of the Western world, it was workers in an industry that first set trends towards automation in motion who showed the power of a traditional general strike in toppling a government.108

For Britain and its declining empire, Iranian oil was an area of imperial anxiety. This was tied up with changing attitudes toward labour and industrialisation, resulting at times in confusing policies. The need to have influence and control, especially after the Second World War and during the Consortium era, was packaged in labour terms. London’s insistence on having a significant say in the Consortium revealed the need to maintain its position. Labour tensions in Britain bore political implications that could affect British balance of payments, which invariably was reflected in British concerns when it came to its standing in Iran. While Britain was acutely aware of its limitations, as revealed during the Suez crisis, it nonetheless insisted on maintaining a say and influence when it came to the Consortium’s attitude towards labour.

When the Consortium began operations in 1954, it soon faced opposition from a local population who had driven BP out of the country only a few years earlier. Attributing this to a crisis of social reproduction, the Consortium pursued several paths of mitigation including downsizing, securitisation and social engineering. Ultimately, however, smaller-scale labour activism continued to embroil the Consortium in local and national politics throughout the 1950s. Therefore, the ‘human factor’ continued to be central to oil operations at a time when it was being increasingly supplanted by automation in other parts of the world, and so the Consortium and British government both failed to achieve their aim of controlling Iranian oil. And ultimately it was because of the refinery’s location in the middle of a large city with a dependent population that automation was not a serious option in Abadan. Rather, new locations for oil operations were required for such ends, far away from urban settlements – perhaps even offshore – where social reproduction could be much more controlled.

- 1. For recent examples see Toby Craig Jones, “After the Pipelines: Energy and the Flow of War in the Persian Gulf”, South Atlantic Quarterly, 116, no. 2, 2017, 417–25; Corey Ross, Ecology and Power in the Age of Empire: Europe and the Transformation of the Tropical World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); and Anand Toprani, Oil and the Great Powers: Britain and Germany, 1914 to 1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019). These studies have revived earlier scholarly interest in this connection exemplified by Marian Kent, Moguls and Mandarins: Oil, Imperialism, and the Middle East in British Foreign Policy 1900-1940 (London: Frank Cass, 1993).

- 2. Christopher R. W. Dietrich, Oil Revolution: Sovereign Rights and the Economic Culture of Decolonization, 1945 to 1979 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 3. As outlined in detail in Giuliano Garavini, The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- 4. The most comprehensive accounts of this are Ervand Abrahamian, The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.-Iranian Relations (New York: The New Press, 2013); Mostafa Elm, Oil, Power, and Principle: Iran’s Oil Nationalization and Its Aftermath (Syracuse, N.Y. : Syracuse University Press, 1992); and, in Persian, Mohammad Ali Movahed, Khab-e Ashofte-ye Naft: Doktor Mosaddeq va Nahzat-e Melli-Ye Iran, volumes 1 and 2 (Tehran: Nashr-e Karnameh, 1378/1999).

- 5. Jones, ‘After the Pipelines’; cf. Nathan J. Citino, From Arab Nationalism to OPEC: Eisenhower, King Sa’ud, and the Making of U.S.-Saudi Relations (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002).

- 6. Since the war, the British Labour government had pushed for the replacement of coal with oil in the local economy, furthering the need to ensure easy access to Iranian oil throughout the late 1940s; see James Bamberg, The History of the British Petroleum Company: Volume 2 The Anglo–Iranian Years, 1928–1954 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 315–316.

- 7. Christopher F. Jones, “The Materiality of Energy”, Canadian Journal of History, vol. 53, no. 3, 2018, 378–94.

- 8. On Barak, Powering Empire: How Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2020); Victor Seow, Carbon Technocracy: Energy Regimes in Modern East Asia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022). Indeed, there is increasing attention on the role of energy in histories of colonialism; see Marta Musso and Guillemette Crouzet, “Energy Imperialism? Introduction to the Special Issue”, Journal of Energy History/Revue d’Histoire de l’Énergie, vol. 3, no. Special Issue: Energy imperialism? Resources, power and environment (19th-20th Cent.), 2020.

- 9. Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2011). For a similar approach that examines the politics of infrastructure in the early US oil industry, see Christopher F. Jones, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- 10. Mitchell, Carbon Democracy, 36–38.

- 11. A similar argument can also be found in Bruce Podobnik, Global Energy Shifts: Fostering Sustainability in a Turbulent Age (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006). As Malm shows, similar considerations to limit workers’ agency lay at the heart of the initial turn to coal as a replacement for water as an energy source; see Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam-Power and the Roots of Global Warming (London: Verso, 2015).

- 12. Cara New Daggett, The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics, and the Politics of Work (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

- 13. Abrahamian, The Coup; Ervand Abrahamian, “The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Labor Movement in Iran, 1941-1953”, in Michael E. Bonine and Nikki R. Keddie (eds.), Modern Iran: The Dialectics of Continuity and Change, (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981), 211–32; Stephanie Cronin, “Popular Politics, the New State and the Birth of the Iranian Working Class: The 1929 Abadan Oil Refinery Strike”, Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 46, no. 5, 2010, 699–732; Kaveh Ehsani, “The Social History of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry: The Built Environment and the Making of the Industrial Working Class (1908-1941)” (Ph.D diss., University of Leiden, Leiden 2015); Rasmus Elling, “A War of Clubs: Inter-Ethnic Violence and the 1946 Oil Strike in Abadan”, in Nelida Fuccaro (ed.), Violence and the City in the Modern Middle East (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2016), 189–210; Touraj Atabaki, “Chronicles of a Calamitous Strike Foretold: Abadan, July 1946”, in Karl Heinz Roth (ed.), On the Road to Global Labour History (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 93–128; Maral Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It, It Should Be Paid to Me”: A Social History of Labour in the Iranian Oil Industry 1951-1973’ (Ph.D diss., Leiden University, Leiden 2017); Peyman Jafari, “Oil, Labour and Revolution in Iran: A Social History of Labour in the Iranian Oil Industry, 1973-83” (Ph.D diss, Leiden University, Leiden, 2018); Nimrod Zagagi, “An Oasis of Radicalism: The Labor Movement in Abadan in the 1940s”, Iranian Studies, vol. 53, no. 5-6, 2020, 847-72.

- 14. Peyman Jafari, “Linkages of Oil and Politics: Oil Strikes and Dual Power in the Iranian Revolution”, Labor History, vol. 60, no. 1, 2019, 24–43; Assef Bayat, Workers and Revolution in Iran: A Third World Experience of Workers’ Control (London: Zed, 1987).

- 15. On social engineering and urban planning see Kaveh Ehsani, “Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns: A Look at Abadan and Masjed-Soleyman”, International Review of Social History, vol. 48, no. 3, 2003, 361–99; Ehsani, “The Social History of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry”; Mark Crinson, “Abadan: Planning and Architecture under the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company”, Planning Perspectives, vol. 12, no. 3, 1997, 341–59. On securitisation in Abadan during the Allied occupation of Iran during the Second World War, see Rasmus Christian Elling and Rowena Abdul Razak, “Oil, Labour and Empire: Abadan in WWII Occupied Iran”, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 50, no.1, 2021, 1–18.

- 16. Mattin Biglari, Refining Knowledge: Labour, Expertise and Oil Nationalisation in Abadan, 1933-1951 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming 2024); cf. Abrahamian, The Coup; and Zagagi, “An Oasis of Radicalism”.

- 17. Barbara Laslett and Johanna Brenner, ‘Gender and Social Reproduction: Historical Perspectives’, Annual Review of Sociology 15 (1989): 381-404, at 383. For a recent appraisal of social reproduction theory see Tithi Bhattacharya (ed.), Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression (London: Pluto Press, 2017).

- 18. This was long ago acknowledged by Marx in his analysis of the reproduction of labour power; see Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1981), 274-76.

- 19. Erik de Gier, Capitalist Workingman’s Paradises Revisited: Corporate Welfare Work in Great Britain, the USA, Germany and France in the Golden Age of Capitalism, 1880‐1930 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).

- 20. Nelida Fuccaro, “Introduction: Histories of Oil and Urban Modernity in the Middle East”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013, 1–6; Nelida Fuccaro, “Arab Oil Towns as Petro-Histories”, in Carola Hein (ed.), Oil Spaces: Exploring the Global Petroleumscape (New York: Routledge, 2021), 129–44; cf. Farah al-Nakib, Kuwait Transformed: A History of Oil and Urban Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016).

- 21. This is the subject of Biglari, Refining Knowledge.

- 22. Touraj Atabaki, Elisabetta Bini, and Kaveh Ehsani (eds.), Working for Oil: Comparative Social Histories of Labor in the Global Oil Industry (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018); Elisabetta Bini and Francesco Petrini, “Labor Politics in the Oil Industry: New Historical Perspectives”, Labor History, vol. 60, no. 1, 2019, 1–7.

- 23. The ‘black box’ of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s technical operations has been well and truly opened, drawing on the insights of STS, in Katayoun Shafiee, Machineries of Oil: An Infrastructural History of BP in Iran (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018). For similar attempts to demystify oil from the vantage point of the humanities and social sciences, see Hannah Appel, Arthur Mason and Michael Watts (eds.), Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas (Ithaca London: Cornell University Press, 2015); and Hannah Appel, The Licit Life of Capitalism: U.S. Oil in Equatorial Guinea (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). For an introduction to the energy humanities, see Imre Szeman and Dominic Boyer (eds.), Energy Humanities: An Anthology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017).

- 24. For example, Shell was able to operate its Deer Park Refinery through a major strike in 1962-63 because of automation; see Tyler Priest and Michael Botson, ‘Bucking the Odds: Organized Labor in Gulf Coast Oil Refining’, Journal of American History, 99, no. 1, 2012, 100–110. Refining and other process industries were the first to experience automation, as outlined in David F. Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation, 2nd edn., (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2011), 58-59.

- 25. ‘Speech at Abadan by Dr. Amini, Minister of Finance, on 30 October, 1954’, box 4971, RG 59, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, USA (hereafter NARA).

- 26. ‘Difficulty Experienced by Oil Operating Companies in Maintaining Labor Discipline’, 31 July 1955 (despatch 43), box 4972, RG 59, NARA.

- 27. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 317–25.

- 28. Rolland Bushner, ‘Work Stoppages at the Iranian Oil Refining Company during the Past Six Months and Their Implications’, 13 October 1955, Folder 560 10RC, RG 84, Box 68, NARA.

- 29. ‘Labor Problems of the International Oil Consortium Operating Companies’, 28 December 1955 (despatch 524), box 4966, RG 59, NARA.

- 30. ‘Personnel Problems of the Consortium of Iranian Oil Operating Companies’, 23 July 1958 (despatch 69), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 31. After the nationalisation, there was great secrecy surrounding the labour force in the south. In October 1958, the Iranian Ministry of Labour and the Plan Organisation conducted a survey of manpower in the country, collecting information on workers that could be used to help improve industrial efficiency. However, when it came to the oil industry, information was declassified and remained unreported. Iranian Manpower Resources and Requirements National Survey, October 1958, LAB13/1093, the National Archives of the UK, Kew, London (hereafter TNA), 21815/4/1/1959.

- 32. ‘Possible Politico-Economic Problems arising from an Increasing Population on Abadan Island’, 20 January 1957, (despatch 8), enclosure 1, box 4973, RG 59, NARA.

- 33. On AIOC’s training policy see Michael E. Dobe, “A Long Slow Tutelage in Western Ways of Work: Industrial Education and the Containment of Nationalism in Anglo-Iranian and Aramco, 1923-1963” (Ph.D diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Jersey, 2008); and Mattin Biglari, ‘Making Oil Men: Expertise, Discipline and Subjectivity in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s Training Schemes’, in Nelida Fuccaro and Mandana Limbert (eds.), Life Worlds of Middle Eastern Oil: Histories and Ethnographies of Black Gold (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023).

- 34. Possible Politico-Economic Problems arising from an Increasing Population on Abadan Island’, 20 January 1957, (despatch 8), enclosure 1, box 4973, RG 59, NARA.

- 35. Ehsani, “Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns”; idem, “The Social History of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry”; Crinson, "Abadan"; Touraj Atabaki, “From ‘Amaleh (Labor) to Kargar (Worker): Recruitment, Work Discipline and Making of the Working Class in the Persian/Iranian Oil Industry”, International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 84, 2013, 159–75.

- 36. J.A. Jameson, ‘Report on a Visit to Iran 1938’, p. 31, BP Archive arcref 67627, University of Warwick, UK (hereafter BP).

- 37. Maral Jefroudi, ‘Revisiting “the Long Night” of Iranian Workers: Labor Activism in the Iranian Oil Industry in the 1960s’, International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 84, 2013, 176–94, at 182.

- 38. ‘Possible Politico-Economic Problems arising from an Increasing Population on Abadan Island’, 20 January 1957, (despatch 8), enclosure 1, box 4973, RG 59, NARA.

- 39. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 173.

- 40. ‘Surplus Labor Problem of the Operating Companies of the International Oil Consortium’, 19 July 1955 (despatch 10), box 4966, RG 59, NARA.

- 41. Despatch 69, box 4974, RG 59, NARA. On the Khuzestan Development Service see Gregory Brew, ‘“What They Need Is Management”: American NGOs, the Second Seven Year Plan and Economic Development in Iran, 1954–1963”, The International History Review, vol. 41, no. 1, 2019, 1–22.

- 42. ‘The Iranian Oil Consortium’s Development of Khark Island and Attendant Problems’, (despatch 31), p. 4, box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 43. See Eva-Maria Muschik, ‘“A Pretty Kettle of Fish”: United Nations Assistance in the Mass Dismissal of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry, 1959–1960’, Labor History, vol. 60, no. 1, 2019, 8–23.

- 44. Rolland Bushner, ‘Work Stoppages at the Iranian Oil Refining Company during the Past Six Months and Their Implications’, 13 October 1955, Folder 560 10RC, RG 84, Box 68, NARA.

- 45. ‘Talking Points: Time Keeping’, Abadan Today, 10 September 1958, Charles Schroeder Files (CSF), http://www.commoncoordinates.com/AbadanInThe50s/.

- 46. ‘Talking Points: Drinking Water’, Abadan Today, 3 September 1958, CSF.

- 47. ‘Talking Points: Be Tidy Minded’, Abadan Today, 27 August 1958; ‘Your Garden’, Abadan Today, 24 September 1958, CSF.

- 48. ‘Khanom, yad begirid monazam bashid ba barnameh-ye sahih had-e aqal kar va had-e aksar natijeh’ (‘Madam, learn to become accustomed to correct planning with minimal input and maximum output’), Aineh, 22 June 1961, CSF.

- 49. For example, see Elisabetta Bini, “From Colony to Oil Producer: US Oil Companies and the Reshaping of Labor Relations in Libya during the Cold War”, Labor History, vol. 60, no.1, 2019, 44–56; and Myrna Santiago, “Women of the Mexican Oil Fields: Class, Nationality, Economy, Culture, 1900–1938”, Journal of Women’s History, vol. 21, no. 1, 2009, 87–110. As Maral Jefroudi argues, social reproduction was essential for the functining of oil operations even beyond women's labour; see ‘“If I Deserve It”’, ch. 3.

- 50. Abrahamian, “The Strengths and Weaknesses”; Abrahamian, The Coup; Elling, “A War of Clubs: Inter-Ethnic Violence and the 1946 Oil Strike in Abadan”; Atabaki, “Chronicles of a Calamitous Strike Foretold"; Zagagi, "An Oasis of Radicalism”.

- 51. ‘Despatch 192, p. 8, box 5498, RG 59, NARA.

- 52. British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, October 1958, LAB13/1093, 21815/4/1/1959, TNA.

- 53. ‘Reported Threats to IORC Installations; Increased Security Planned’, 3 August 1957 (despatch 5), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 54. ‘Memorandum of Conversation with S. K. Kazerooni’, 7 March 1958 (despatch 28), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 55. Peyman Jafari, “Reasons to Revolt: Iranian Oil Workers in the 1970s”, International Labor and Working-Class History, vol. 84, 2013, 195–217, at 209-10.

- 56. Bamberg, The History of the British Petroleum Company: Volume 2, 432–433.

- 57. Quoted from Bamberg, The History of the British Petroleum Company: Volume 2, 494.

- 58. Cabinet memorandum (Eden), 5 January 1954, CAB 129/65/3, C (54) 3, TNA.

- 59. Steven G Galpern, Money, Oil, and Empire in the Middle East: Sterling and Postwar Imperialism, 1944–1971 (Cambridge University Press, 2009), 130–132.

- 60. Cabinet memorandum (Eden), 8 November 1954, CAB 129/71/35, C (54) 335, TNA.

- 61. Secretary of State (Lloyd) to Prime Minister (Churchill), 6 August 1954, FO800/814, PM/MS/54/120, TNA; Eden enjoyed close personal relations with the Iranian ambassador to London, Ali Soheili, whom Eden noted for his refusal to serve the Musaddiq government. Foreign Office (Eden) to British Embassy Tehran (Stevens), 17 March 1954, FO800/814, Per/54/4, TNA.

- 62. Soheili wanted advice with regards to the Soviet Union, Turkey, and Pakistan. Foreign Office (Eden) to British Embassy Tehran (Stevens), 17 March 1954, FO800/814, Per/54/4, TNA.

- 63. Some continuity even existed at a diplomatic level when Eden wanted to appoint RMA Hankey as ambassador. Hankey had served as First Secretary at the British Legation during the occupation. Secretary of State (Eden) to Prime Minister (Churchill), 14 October 1953, FO800/814, PM/53/309, TNA.

- 64. Standard Oil of New Jersey also noted that the British were under the influence of colonial government. Galpern, Money, Oil, and Empire in the Middle East, 140–141.

- 65. Elling and Abdul Razak, “Oil, Labour and Empire: Abadan in WWII Occupied Iran”, 8.

- 66. Foreign Office (Wright) to Ministry of Power (Ayres), 10 July 1959, T236/5879, 143 TNA.

- 67. Relationship between HM Government and the British Petroleum Company Limited, January 1960, T236/5879, 148, TNA.

- 68. Minister of Power (Mills) to Treasury Chambers (Amory), 4 May 1959, T236/5879, 114, TNA.

- 69. Foreign Office (Ormsby-Gore) to Minister of Power (Mills), 14 May 1959, T236/5879, 124, TNA.

- 70. Minister of Power (Corley) to Treasury Chambers (Bell), 24 August 1959, T236/5879, 146, TNA.

- 71. Relationship between HM Government and the British Petroleum Company Limited, January 1960, T236/5879, 148, TNA.

- 72. In the case of Gibraltar, Monckton presented ways in which income discrimination between Spanish and British workers could be corrected. However, there were still objections between government departments over the necessity to do this. Cabinet memorandum (Monckton), 24 July 1954, CAB 129/70/3, C. (54) 253, TNA.

- 73. Cabinet memorandum (Monckton), 18 January 1954, CAB 129/65/2, C. (54) 21, TNA.

- 74. This was particularly apparent during the October 1954 dock strikes, when the ministry even considered calling in the military to stand in for the striking workers. Cabinet memorandum, 28 October 1954, CAB 128/27/71, C.C. (54), TNA.

- 75. John Darwin, Britain and Decolonisation: The Retreat from Empire in the Post-War World (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1988), 223; See also, Danny Steed, British Strategy and Intelligence in the Suez Crisis (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

- 76. Darwin, Britain and Decolonisation, 224–225.

- 77. Ronald Hyam, Britain’s Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918-1968 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 288–289.

- 78. ‘Labor Affairs in Iran, 1957’, 15 March 1958, p. 4, RG 59, Box 4966, NARA.

- 79. Interview with Manuchehr Parsa, Iran Petroleum Museum Oral Histories, 28 November 2016, http://www.petromuseum.ir/content/1/اطلاع-رسانی/1252/گفت-و-گو-با-منوچهر… (Accessed 01/05/2022).

- 80. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 138.

- 81. ‘Employees of the National Iranian Oil Company and the Consortium Complain About the Conditions of Their Employment’, 4 February 1959, Ettela’at.

- 82. Shafiee, Machineries of Oil, ch. 4; Biglari, Refining Knowledge, ch. 3.

- 83. ‘Flash Fire in the Abadan Refinery’, 4 September 1959 (despatch 18), box 4975, RG 59, NARA.

- 84. ‘Abadan Branch of the Society of Iranian Engineers’, 23 June 1958, RG 59, Box 4974, NARA.

- 85. ‘Survey and Recommendations of the Status and Potential of the Abadan Technical Institute’, 1956, Box 130, Ralph Cooper Hutchison Papers, Library of Congress (LoC), Washington, DC.

- 86. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 219-23.

- 87. Majid Javaheriʹzadeh, Palyeshgah-e Abadan dar 80 Sal Tarikh-e Iran 1908-1988 (Tehran: Nashr-e Shadegan, 2017); Jefroudi documents the same meeting in ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 159-60.

- 88. Telegraph, 24/3/1338 (15 June 1959), no. 169, file 2111436, Library, Museum, and Document Centre of Iran Parliament.

- 89. Robert E. Gordon, ‘Tentative Plan for Alleviation of IORC’s Surplus Labor Problem’, 25 March 1958, RG 59, Box 4974, NARA.

- 90. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 157-58.

- 91. For a detailed account of these strikes see Ibid., 320–28.

- 92. British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, 31 July 1959, LAB13/1093, L.A.18/32/58, TNA.

- 93. Review of Labour Affairs in Iran, July – December 1958 (Read), 6 February 1959, LAB13/1093, TNA.

- 94. British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, 18 June 1959, LAB13/1093, 21815/12/59, TNA.

- 95. Jefroudi, ‘Revisiting “the Long Night” of Iranian Workers’. On the history of Iran's labour laws see Habib Ladjevardi, Labor Unions and Autocracy in Iran (Syracuse, N.Y. : Syracuse University Press, 1985).

- 96. Rolland Bushner, ‘Work Stoppages at the Iranian Oil Refining Company during the Past Six Months and Their Implications’, 13 October 1955, Folder 560 10RC, RG 84, Box 68, NARA.

- 97. Priest and Botson, ‘Bucking the Odds’.

- 98. Jalal Al-Ahmad, Gozaresh-ha: Majmu’eh-ye Gozaresh, Goftar, Safarnameh-ha-ye Kutah (az 1337 ta 1347), ed. Mostafa Zamani-Nia (Tehran: Ferdows, 1376/1997), 80. On Al-e Ahmad's intellectual oeuvre see Ali Mirsepassi, Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 97–114.

- 99. ‘Visit to Abadan Oil Refinery and Consortium Fields’, 31 March 1958 (despatch 868), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 100. Jefroudi, ‘“If I Deserve It”’, 317.

- 101. Despatch 69, box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

- 102. J. H. Bamberg, British Petroleum and Global Oil, 1950-1975: The Challenge of Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 281.

- 103. Joost Jonker and Stephen Howarth, A History of Royal Dutch Shell, Volume 2: Powering the Hydrocarbon Revolution, 1939-1973 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 265.

- 104. Hyam, Britain’s Declining Empire, 289.

- 105. Jonket and Howarth, A History of Royal Dutch Shell, Volume 2, 274.

- 106. Ibid, 278-79.

- 107. For example, see Zachary Davis Cuyler, “Tapline, Welfare Capitalism, and Mass Mobilization in Lebanon, 1950-1964”, in Touraj Atabaki, Elisabetta Bini, and Kaveh Ehsani (eds.), Working for Oil: Comparative Social Histories of Labor in the Global Oil Industry (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 337–68.

- 108. For example, George Mallet’s observations of the CalTex’s Bec d’Ambès refinery in 1958 formed the basis for his ‘new working class’ hypothesis; see George Mallet, The New Working Class (Nottingham: Spokesman Books, 1975).

Primary Sources

British Petroleum Archives, University of Warwick (BP), Jameson, J.A., ‘Report on a Visit to Iran 1938’, p. 31, BP Archive arcref 67627, BP.

Iran Petroleum Museum Oral Histories, Interview with Manuchehr Parsa, Iran Petroleum Museum Oral Histories, 28 November 2016, http://www.petromuseum.ir/content/1/اطلاع-رسانی/1252/گفت-و-گو-با-منوچهر… (Accessed 01/052022).

Library of Congress, Washington DC, Survey and Recommendations of the Status and Potential of the Abadan Technical Institute’, 1956, Box 130, Ralph Cooper Hutchison Papers, Library of Congress (LoC), Washington, DC.

Library, Museum, and Document Centre of Iran Parliament, Tehran, Telegraph, 24/3/1338 (15 June 1959), no. 169, file 2111436, Library, Museum, and Document Centre of Iran Parliament.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Abadan Branch of the Society of Iranian Engineers’, 23 June 1958, RG 59, Box 4974, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), Bushner, Rolland, ‘Work Stoppages at the Iranian Oil Refining Company during the Past Six Months and Their Implications’, 13 October 1955, Folder 560 10RC, RG 84, Box 68, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), Despatch 69, box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), Despatch 192, p. 8, box 5498, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Difficulty Experienced by Oil Operating Companies in Maintaining Labor Discipline’, 31 July 1955 (despatch 43), box 4972, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Flash Fire in the Abadan Refinery’, 4 September 1959 (despatch 18), box 4975, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), Gordon, Robert E., ‘Tentative Plan for Alleviation of IORC’s Surplus Labor Problem’, 25 March 1958, RG 59, Box 4974, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Labor Affairs in Iran, 1957’, 15 March 1958, p. 4, RG 59, Box 4966, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Labor Problems of the International Oil Consortium Operating Companies’, 28 December 1955 (despatch 524), box 4966, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Memorandum of Conversation with S. K. Kazerooni’, 7 March 1958 (despatch 28), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Personnel Problems of the Consortium of Iranian Oil Operating Companies’, 23 July 1958 (despatch 69), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Possible Politico-Economic Problems arising from an Increasing Population on Abadan Island’, 20 January 1957, (despatch 8), enclosure 1, box 4973, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Reported Threats to IORC Installations; Increased Security Planned’, 3 August 1957 (despatch 5), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Speech at Abadan by Dr.Amini, Minister of Finance, on 30 October, 1954’, box 4971, RG 59, NARA

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Surplus Labor Problem of the Operating Companies of the International Oil Consortium’, 19 July 1955 (despatch 10), box 4966, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘The Iranian Oil Consortium’s Development of Khark Island and Attendant Problems’, (despatch 31), p. 4, box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, (NARA), ‘Visit to Abadan Oil Refinery and Consortium Fields’, 31 March 1958 (despatch 868), box 4974, RG 59, NARA.

Newspapers

Aineh, 22 June 1961, Charles Schroeder Files (CSF).

‘Employees of the National Iranian Oil Company and the Consortium Complain About the Conditions of Their Employment’, 4 February 1959, Ettela’at.

‘Talking Points: Time Keeping’, Abadan Today, 10 September 1958, Charles Schroeder Files (CSF), http://www.commoncoordinates.com/AbadanInThe50s/.

‘Talking Points: Be Tidy Minded’, Abadan Today, 27 August 1958;

‘Your Garden’, Abadan Today, 24 September 1958, CSF.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, 18 June 1959, LAB13/1093, 21815/12/59, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, 31 July 1959, LAB13/1093, L.A.18/32/58, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), British Embassy Tehran (Read) to Ministry of Labour and National Service, October 1958, LAB13/109, 21815/4/1/1959, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Cabinet memorandum (Monckton), 18 January 1954, CAB 129/65/21, C. (54) 21, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Cabinet memorandum (Monckton), 24 July 1954, CAB 129/70/3, C. (54) 253, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Cabinet memorandum, 28 October 1954, CAB 128/27/71, C.C. (54), TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Cabinet memorandum (Eden), 8 November 1954, CAB 129/71/35, C (54) 335, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Foreign Office (Eden) to British Embassy Tehran (Stevens), 17 March 1954, FO800/814, Per/54/4, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Foreign Office (Ormsby-Gore) to Minister of Power (Mills), 14 May 1959, T236/5879, 124, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Foreign Office (Wright) to Ministry of Power (Ayres), 10 July 1959, T236/5879, 143, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Iranian Manpower Resources and Requirements National Survey, October 1958, LAB13/1093, 21815/4/1/1959, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Minister of Power (Corley) to Treasury Chambers (Bell), 24 August 1959, T236/5879, 146, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Minister of Power (Mills) to Treasury Chambers (Amory), 4 May 1959, T236/5879, 114, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Relationship between HM Government and the British Petroleum Company Limited, January 1960, T236/5879,148, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Review of Labour Affairs in Iran, July – December 1958 (Read), 6 February 1959, LAB13/1093, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Secretary of State (Eden) to Prime Minister (Churchill), 14 October 1953, FO800/814, PM/53/309, TNA.

The National Archives of the UK, Kew, (TNA), Secretary of State (Lloyd) to Prime Minister (Churchill), 6 August 1954, FO800/814, PM/MS/54/120, TNA.

Secondary Sources

Abrahamian, Ervand, The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.-Iranian Relations (New York: The New Press, 2013).

Abrahamian, Ervand, “The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Labor Movement in Iran, 1941-1953”, in Michael E. Bonine and Nikki R. Keddie (eds.), Modern Iran: The Dialectics of Continuity and Change, (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1981).

Al-Ahmad, Jalal, Gozaresh-ha: Majmu’eh-ye Gozaresh, Goftar, Safarnameh-ha-ye Kutah (az 1337 ta 1347), ed. Mostafa Zamani-Nia (Tehran: Ferdows, 1376/1997).

Al-Nakib, Farah, Kuwait Transformed: A History of Oil and Urban Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016).